Adam Osborne Interview by Practical Computing (1983)

Osborne reveals his philosophy

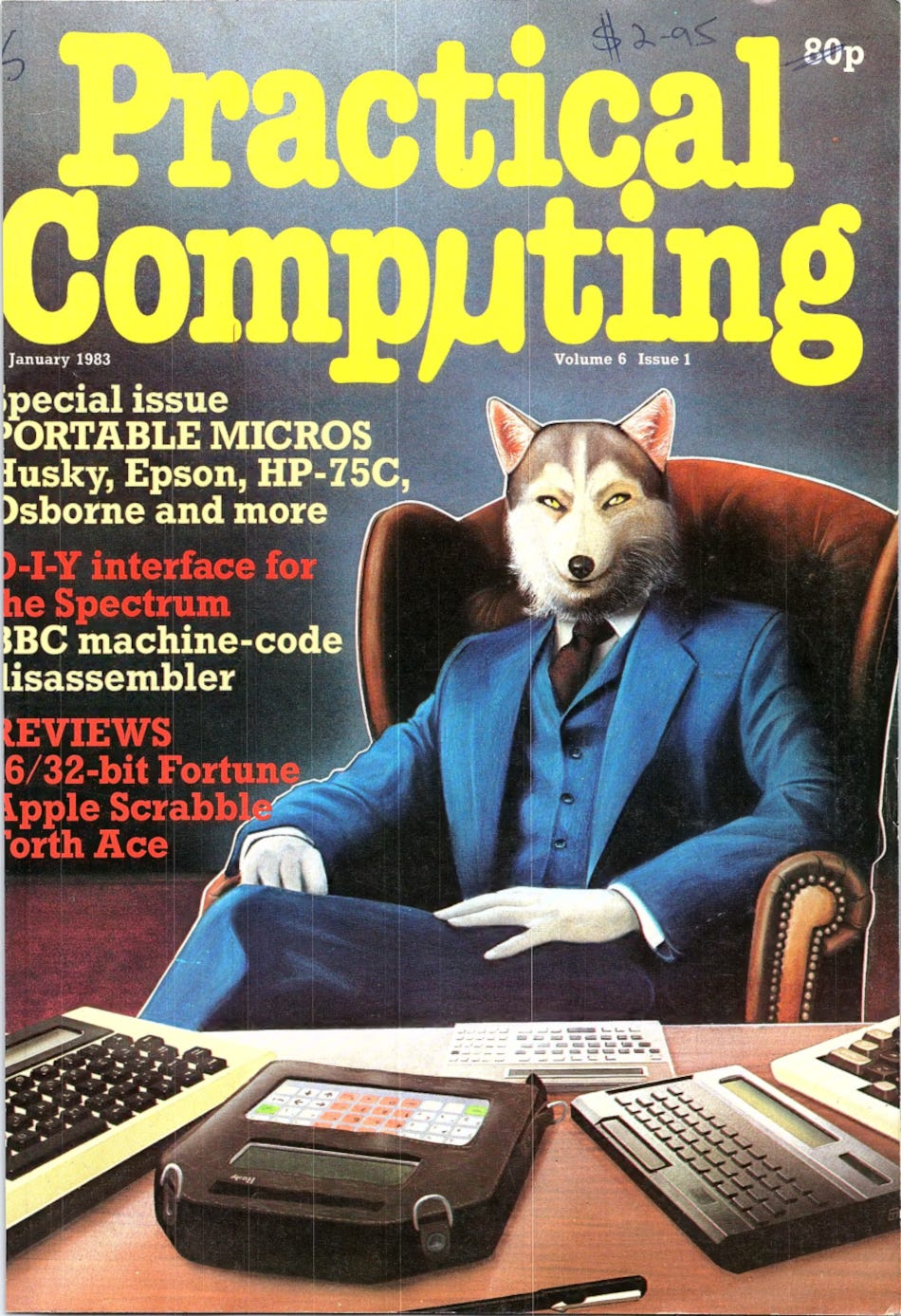

from the January 1983 issue of Practical Computing

Since I’ve been behind for the last couple of months, I’ve decided to give you guys another interview to make up for it. I’ve always been interested in Osborne, so this article is very interesting. Enjoy!

They all laughed, but...

Osborne Computer Corporation is one of the few new start-up companies to succeed in breaking through into the microcomputer big league. Apple, Tandy, Commodore and the other big-name companies have all been around since the earliest days of the microcomputer, and are only now being seriously challenged by the established giants of the large computer world, like IBM and DEC. As a new start-up company the scale and rapidity of Osborne’s success is unique.

Only selling its first machine in June 1981, Osborne now claims 50,000 systems out with users, and a target turnover of one billion dollars by 1984 looks increasingly attainable: 1982 turnover will be around $100 million. The company is shipping 500 units a day from its two U.S. plants.

All this has been achieved on the back of a single product, the Osborne 1 portable computer. Weighing 24lb. including screen and twin disc drives, this mains-powered CP/M system costs £1,250 in the U.K. The price includes software, such as WordStar and SuperCalc, and a manual which rewrites in one compact volume all the necessary documentation.

When Adam Osborne announced his plans to set up a company to bring out the Osborne | he was greeted with much scepticism within the industry. Would people really want such a machine, even allowing for the low price and free software? Its runaway success in the U.S. demonstrated that they did and clearly Adam Osborne is the right person to talk to about what makes the portable computer market tick: “Portability is extremely important. Not so much because people want to hike across the country with a computer or fly around with it, but just to carry it from one room to another without having it all fall apart with wires and cables tangling up all over the place.

“We are going after a consumer market right now and there never really has been a consumer computer. Computers are still designed by people who are computer people. Now that can’t go on for ever. If you want to sell microcomputers in the volumes that we are talking about you have got to start selling to Mr Joe in the street, who has absolutely no desire to own a computer but is buying the device for what it can do for him. They are buying a solution, they are buying a computer the way they might a typewriter, or a vacuum cleaner. That means it has got to have the level of reliability, be that easy to use, and be that easy to learn to use. They are never going to program the thing. It has got to be just solid, rugged and self-evident. We have come a long way but we have a way to go yet.”

The Osborne is not everyone’s idea of a portable computer: "as portable as a suitcase full of bricks" is one description. "The thing you’ve got to look at right now is not getting the weight of the machine down to one pound but the fact that the keyboard has to be large enough for normal fingers. And that sets one limit right there. Another limit is that you have got to have a screen that you can look at, and ours is about the bottom limit of that, you can’t get much smaller than we have."

What does Osborne think of machines like the Epson, which has a liquid-crystal display of four rows of 20 columns and weighs only 4lb. "It is a different market again. You could not hope to do word processing on it or reasonably expect to do electronic spreadsheet work with that. But you could very reasonably expect to do scientific calculations — something that is computational intensive. In the days when I was a chemical engineer I would have had no trouble with a thing like that. I would have done nice little programs and watched them churn away.

“I had a Radio Shack pocket computer with a single-line display I ended up giving to a friend of mine, a civil engineer, he loves it."

Osborne prices have from the outset been pitched low. Is this some long-term strategic policy to buy a slice of the market or is it profitable anyway? "It is profitable anyway. By going in low we do expect to get a high volume, and we have achieved that. You are obviously not going in at that kind of price expecting to make a profit after you have shipped 10 machines a month as some other companies may decide to do. We are looking for reasonable volumes, but the volumes are quite easy to achieve."

Never ever

Some companies like Hewlett-Packard have a diametrically opposed approach. At the recent press-conference launching of HP’s own new portable, the HP-75C, an HP executive said openly that Hewlett-Packard would never bring out an inexpensive machine. Adam Osborne can see the logic behind this. "HP sell quality and service to a market that is not particularly price sensitive. For a long time their customer base has been large corporations who want to make sure that the thing is reliable and does the job it is supposed to do. They have never been very successful in consumer products — even their calculators have not really been that successful as general run-of-the-mill consumer products. They still sell most of their calculators and everything else to large companies. And large companies, quite honestly, are not price sensitive."

Programming policy

Osborne employs very few programmers. From the beginning the Osborne philosophy has been to buy in software. Out of approximately 350 employees around the world less than a dozen are programmers. "This is not many compared to most other companies. We need them to tailor operating systems to particular configurations and to do diagnostics, that kind of very low-level engineering type of software. We don’t develop our own operating systems, languages or application programs."

Instead Osborne buys in software from outside sources, choosing well-established standard software. "Occasionally where we knew that the software we needed didn’t exist we went out and instigated it. SuperCalc was our invention. We went to Sorcim and said do this program for us and they did. But in most cases the software does already exist."

But will it continue to exist as the market grows? Will there ever be a software crisis? "No. I’m quite certain it will continue to exist in excess because everybody is busy writing programs, and even though most of it is junk it doesn’t take but two or three percent of the people writing programs to produce something useful, and we are all in good shape."

But do they produce things that can be picked up and used readily by people new to computers? "That is the difference between the one that succeeds and the one that does not."

Obsolescence

CP/M is now getting to be an old operating system, and might be seen to be coming to the end of its life. Osborne does not think so. "I argue it is not coming to the end of its life, and the reason it is not is that it is still perfectly adequate for everything people try to do with it. The end-user can frankly see little or no difference between a program written under CP/M and a program written under a far more efficient operating system. This is the big difference from having an obsolete machine, like the Apple II, where the user will see very definitely the price/performance difference, and won’t continue to put up with 40-column displays, wires all over the place or boards for this, that and the other. These are perceived differences. You can say that CP/M is an obsolete operating system but there is no perceived difference. And as for the programmers, they don’t care, they are interested in what can sell. They might yell and bitch but then take Basic, which was an obsolete language in 1969, but it is adequate. The end-user doesn’t see the difference so it survives."

Where does Unix fit in? "Unix is significant because in the 16-bit world there is no leader. CP/M-86 is around but it certainly hasn’t dominated the 16-bit world, nor has any other operating system done so yet, and one of them is going to. Unix stands a damn good chance.

“In fact in many ways once you start getting down to these consumer computers, once you start loading it up with features you hurt yourself, you don’t help yourself. I’ve got a couple of favourite sayings with regard to software. One of them is ‘Better is the enemy of good’; the other one ‘Adequacy is sufficient, everything else is irrelevant’."

The Osborne approach is to satisfy 90 percent of the users’ needs rather than come unstuck trying to attain 100 percent. "Far the most important thing is making the product something the user is not intimidated by. You start telling the user to buy this machine because you can be running three programs at once and you will lose the user. He doesn’t want that. He is confused, he wonders if he will ever learn to use the son-of-a-bitch. He will go and get something nice and simple instead.”

Adam Osborne derives his certainty about what the user wants from his experience as a journalist. His syndicated column "From the Fountainhead" appeared in many of the new magazines appearing in the United States as the micro boom began. He was widely read by people in the semiconductor and computer business as well as new users. He exposed widespread fraud in the computer-kit business, where customers were sold dud components which they would assume they themselves had damaged while assembling the kit. Osborne stopped writing the column in 1980 when he set up Osborne Computers.

How does Adam Osborne go about deciding what the user now wants from his company. "I would say it is the obvious filtered through my feel for the way the industry is going. A lot of it is obvious — I mean we want more capacity on the diskettes, we want bigger screens with larger displays, we want lower cost, we want lower weight. A lot of this stuff is very straightforward."

Osborne is not very worried by the competition the Osborne 1 is beginning to run into. "As they are following us they have to find a different niche on one side or the other, or else try to beat us on price. Beating us on price has got to be a losing proposition. In order to beat us on price they have got to be able to come in and hit the high volumes as quickly as we did or bankroll, with the assumption that they are going to have significant losses for some time."

But some companies might indeed be prepared to bankroll a new product, particularly the large Japanese companies. Is Osborne impressed with the Japanese performance so far? "Not right now. Give them time, when the new-product cycle slows down sufficiently so that if it takes you three years to develop a product and you still have a winner, then the Japanese are going to be formidable. We have that much time.

“The point is that the Japanese are as perplexed and bewildered by us in America as we are by them. We have been approached by some of the major manufacturers in Japan, wondering if there was a possibility of some kind of joint venture, because they have looked at our product and said ‘My God, we are sure we can build this thing. We would not have ever done so because we would have thought anyone who did it was mad. But obviously we were wrong.’ You see, it is marketing."

Apple has been predicting a major shake out soon in the microcomputer market because there are very large production capacities being brought into play, and the market is becoming reasonably defined. If this scenario is true, how will Osborne survive? "We have to achieve a large base now. The market is still in a transitional phase for a few more years. Now I am not particularly concerned about shake outs at the moment, the reason being that however large the microcomputer market may appear right now I doubt if it’s 10 percent of what it potentially will be. So again for a few more years if you can build it you can sell it, as long as it has any form of viability at all. It is an extremely forgiving market still. It will get much less so within a couple of years."

Being first into a new market carries with it some risks. But Adam Osborne is not worried about pioneering a concept which other people then exploit. "I have and I am being copied and I should be. The more I am copied the more people say this is a legitimate market that we should pay a lot of attention to. I don’t expect to keep 100 percent of this market."

When in two or three years time a very large base of Osborne products has been established, what is to prevent pirated copies or look-alike machines of a legitimate nature coming along and taking that user base? This is already happening with Apple to some extent. "The point is that they are always going to be somewhat behind us. If they actually directly copy our boards we can get them because the law does protect us there, but if they come up with something that is functionally equivalent we can’t. It is just up to us to market better, distribute better, and manufacture more cheaply, which I think we can do."

Organisation not innovation

Osborne is not putting his trust in technical innovation, but in building up a strong organisation. "That’s right. There is nothing to stop you or anyone else going into competition with General Motors if you choose to. There is nothing innovative about their cars."

There is one company that Osborne thinks can succeed at the consumer end of the market — Sinclair. "I have a deep respect for Clive Sinclair. I think that the British Establishment has been unbelievably naive and incredibly stupid in the way it has treated the man. The lot of them have less sense than Clive Sinclair has in his small finger. If they would pay a little bit more attention to the few such people who are around in this country and a lot less attention to disasters like Inmos, this country would be in far better shape in the microcomputer world."

Like Osborne, Clive Sinclair has created a company that has broken into the microcomputer market some time after the easier early days. The fact that Sinclair did this after running into problems with his innovative Black Watch product only makes it more of an achievement, according to Osborne. "His problem was that he went into it with little experience of manufacturing. There was nothing wrong with his ideas, what was wrong was that he did not have a good manufacturing team. And it is a real testimony to the tenacity of that man that he came back and did it again having learnt from his mistakes, this time letting Timex build for him."

Osborne cannot understand why Sinclair has so little recognition in his own country. "I was just reading over the weekend an interview that Prince Charles gave. He was talking about how he wants to be able to instigate innovation. Prince Charles should just go and look at Clive Sinclair and see what that guy is doing. It is going on over here right under the man’s nose. But because he doesn’t fit the exact model — I don’t know what he has done — but for some reason the British Establishment has decided that he doesn’t know what he is doing. The man is going to sell half a million computers this year. And this is a guy who they wrote off a few years ago because he had a good idea but no one would give him the manufacturing backing to finish it off. As far as I am concerned the man is brilliant."

A bunch of whores

At the opposite end of the market what does Adam Osborne think is going to happen with the very large computer companies. Some, like NCR and Burroughs, have not yet established a strong base in the micro market.

"I think all of those companies are ultimately going to look for their own entry into the personal computer market, in one form or another. The market for very big computers is obviously going to be quite stagnant in comparison to the market for very small computers. These guys have a lot of cash. And it’s a question of them figuring out what they want to do. A lot of us in the microcomputer world are a bunch of whores, we all have our price.”

Does this mean that an offer to buy Osborne would be accepted? "We all have our price. If they came along and offered me two billion dollars for it right now — where’s the contract? I think the chances are more likely that we would go public first."

Stocks and shares

Osborne is not yet a quoted company. This means that whether or not the company is bought out now, once Osborne Computer Corporation goes public Adam Osborne as a major shareholder stands to become very rich. And not just Osborne himself, some 200 out of the 350 or so employees have stock options, which would probably net them tidy sums as well. "You normally have to be in the company six months before you have a stake in it so the international employees, apart from some of the senior managers, are not very well represented as stockholders.

"The way a stock option works — it is something that has been established under American law as an incentive program — is that you are given the right at any time in the future to buy shares at some fixed price, and in a rapidly growing company by the time you get to execute that option usually the fixed price is negligable compared to the current market value. In that way you in effect get the shares free.

"Some of the kids who came in really way up at the beginning can finish up with substantial sums of money. By American law stock options have to be limited to somewhere in the region of 15 percent, and that is around where we will be by the time we go public."

McGraw-Hill bought Adam Osborne’s previous company Osborne Associates which published books mainly by Osborne himself, such as the bestselling series "An Introduction to Microcomputers" and “Running Wild". Osborne now has no involvement in publishing, but is writing a novel. "I’m just proofing the manuscript. I haven’t got a title for the book yet. I have a theory that history has cycles, and that we are on the way out of the present cycle of democracy into a new autocratic era of stability where nothing changes. And this will happen because, given the changes we have seen through technology in the past two decades, people are going to come to the point where they are willing to trade in their expectations and hopes for something better, in exchange for a guarantee of what they have got.

“People will rebel against technology. They will accept what exists but they will except nothing new, and there will be no more technical innovation. People will shun democracy for autocracy. They will once again accept Lords, Barons in some countries, and corporate dictators in others because that is the price of stability.

"I think the world is completely out of control now.”

Since Osborne was born

Adam Osborne was born in Bangkok of British parents. He spent his early childhood in India and Thailand, where his father was a journalist, teacher and counter-missionary, converting Christians back to Hinduism. Adam was sent to England to be educated, and from grammar school went to Birmingham University where he studied chemical engineering.

After completing his PhD in chemical engineering at the University of Delaware he decided to stay in the U.S. and worked for six years as a chemical engineer before deciding to commit himself fully to computing.

He set up Osborne Associates in 1970 to provide programming and technical writing services to the booming computing and semiconductor industries. The writing side took off dramatically in 1975 with the success of his book series "Introduction to Microcomputers”. Adam Osborne became an influential columnist in the newspapers and magazines of the new microcomputer industry.

The publishing giant McGraw-Hill bought Osborne’s flourishing book empire in 1979, providing him with the money to set up his next venture, Osborne Computer Corporation, in January 1981. The first of the new Osborne 1 computers was shipped in June 1981 and the machine made it to Britain in February 1982. It is now the top-selling machine in its class on both sides of the Atlantic.

Adam Osborne is now aged 43 and a U.S. citizen. He has three children, is about to remarry and lives in the San Francisco Bay area. He was interviewed during a brief visit to Osborne Computer Corporation’s U.K. base at Milton Keynes.

What computer ads would you like to see in the future? Please comment below. If you enjoyed it, please share it with your friends and relatives. Thank you.