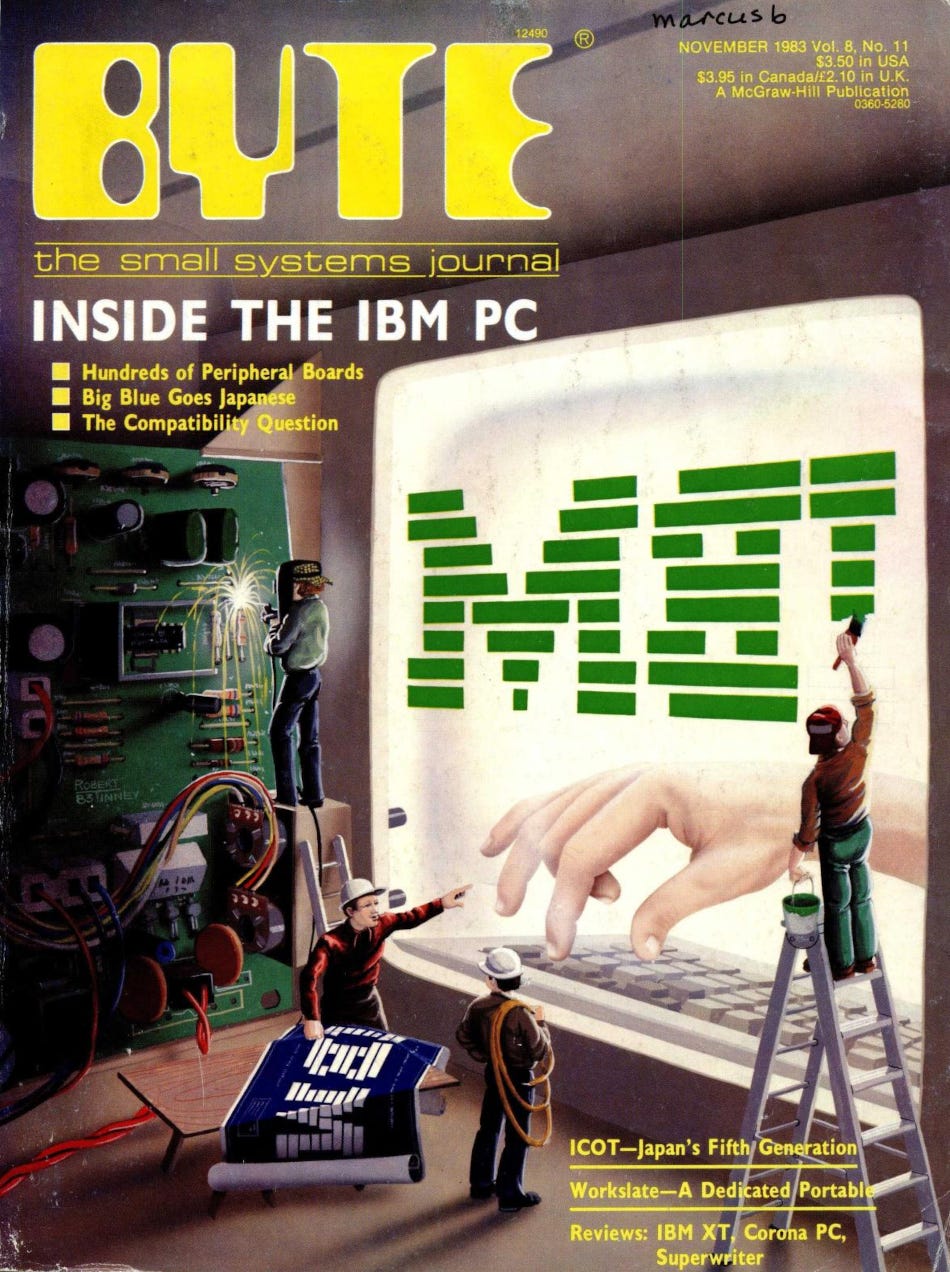

Byte Interviews IBM's Philip D. Estridge (1983)

They dig into the IBM PC.

To make up for the lack of articles this month, I’m posting a big interview that I’ve been waiting to put up. The Osborne Vixen + post will be coming very soon. I’ll try to get more posts done in September.

from the November 1983 issue of Byte magazine

IBM's Estridge

The president of IBM's Entry Systems Division talks about standards, the PC’s simplicity, and a desire not to be different

by Lawrence J. Curran and Richard S. Shuford

The desire to offer a system that would appeal to experimenters who would be able to add value easily was one of the motivations that guided designers at International Business Machines (IBM) Corporation when it undertook development of the IBM Personal Computer (PC) in 1980. Philip D. Estridge, president of the IBM Entry Systems Division in Boca Raton, Florida, explained that desire to develop what is called an "open system" to BYTE editors in a recent interview.

IBM wanted to provide a simple system that offered customers the ability to experiment with very little effort, Estridge says. He adds that the idea for a system that customers could easily apply as they saw fit had been implemented by other personal computer manufacturers.

Simplicity was a key consideration in the IBM PC design, but counterbalancing simplicity was the need for a product that had durability as well as enough capacity and power to grow. The latter considerations immediately led to the selection of a 16-bit processor, says Estridge, who notes that the Intel 8088 was a particularly fortuitous choice: "It happened to be there when we needed it to introduce the power of a 16-bit computer and keep the affordability of the 8-bit I/O [input/output] architecture" Estridge explains that the 8-bit I/O architecture makes it simple for users to add equipment to the IBM PC "without doing a lot of work or spending a lot of money" because the 8-bit interfaces are easy for hobbyists and third-party add-on manufacturers to understand.

Estridge would not discuss unit shipments or dollar sales of the IBM PC, and he would not talk about future IBM product plans or competitive products when he spoke with Richard S. Shuford, BYTE's special projects editor, and Lawrence J. Curran, editor in chief. BYTE's questions are in boldface and Estridge's answers are in lightface.

Did you consider what impact the IBM PC would make in terms of establishing standards?

When we first conceived the idea for the personal computer in 1980, we talked about IBM being in a special position to establish standards, but we decided that we didn't want to introduce standards. We tried to do everything we could to understand the existing infrastructure and propensities [in personal computers] across the board— in marketing, distribution techniques, pricing, customer alternatives, software suppliers, hardware add-on suppliers, and peripheral manufacturers. We tried to fit into what has become a very exciting, well-structured, and well-working business. We firmly believed that being different was the most incorrect thing we could do. We reached that conclusion because we thought personal computer usage would grow far beyond any bounds anybody could see back in 1980. Our judgment was that no single software supplier or single hardware add-on manufacturer could provide the totality of function that customers would want. We didn't think we were introducing standards. We were trying to discover what was there and then build a machine, a marketing strategy, and distribution plan that fit what had been pioneered and established by others in machines, software, and marketing channels.

There is a 3.9-inch disk drive in the IBM family that is not the same size as some of the more popular drives that are becoming de facto standards; is that of concern to IBM?

I can only tell you what we're doing in the personal computer group. There are many activities within IBM. Each has its own goals, and I wouldn't comment on what they're doing. But when we were developing the product in 1980 and 1981, alternative disk sizes were emerging— 3 1/2-inch, 3.9-inch, and 5 1/4-inch. But then you look at the tremendous number of people who manufacture the 5 1/4-inch media, the number who have equipment that produces the reproduced programs, and the number of customers who have the media, and you have to conclude that you don't need to take on the extra burden of introducing a disruptive medium, no matter how good it is. None of the disk alternatives offered enough of an advantage to warrant that kind of disruption. [IBM withdrew this drive from the market in September.]

What were the software considerations that resulted from your desire to "fit in" with the PC?

Let's take BASIC as an example. IBM has an excellent BASIC— it's well received, runs fast on mainframe computers, and it's a lot more functional than microcomputer BASICs were in 1980. But the number of users was infinitesimal compared to the number of Microsoft BASIC users. Microsoft BASIC had hundreds of thousands of users around the world. How are you going to argue with that? Many who wrote about the IBM PC at the beginning said that there was nothing technologically new in this machine. That was the best news we could have had; we actually had done what we had set out to do.

Did you try to discipline yourselves not to stretch the state of the art with the PC?

Yes. For example, you can handle a higher-performance I/O device with a 16-bit I/O channel than you can with an 8-bit I/O channel. Having an 8-bit I/O channel inherently limits the performance of the main processor because you have to move twice as many bits per operation. But that was a trade-off we chose to make to fit into what was already there. It wasn't too difficult a trade-off to make because there were no programs— and there are still few— that demand a higher performance processor than most that are out there.

Do you have a profile of your typical customer or user?

I don't think we have a typical user because the machine is so communal that typical doesn't have meaning, except for the fact that more and more people are discovering that they have needs that can be answered rather nicely by a personal computer. And they are in all walks of life— all the way from very young children to very elderly people— in every profession.

Is there a typical minimum configuration emerging?

I don't know. We've forced that answer somewhat because we build the machines that are most frequently ordered. We build four or five configured systems to make it easy for the dealer to put the systems together so that the work is done partly by us and partly by the dealer. We know that there are a lot of people building complete machines starting with a very rudimentary form of our product.

You say that you don't have a typical user, but is there a set of typical user characteristics that you have to deal with? For instance, do you find people who don't want to type on the machine because of the keyboard?

Yes, we find those reactions, but not quite the way you said it.

Some people are upset about the placement of the left-hand Shift key and the Return key.

I wasn't thrilled with the placement of those keys, either. But every place you pick to put them is not a good place for somebody, and it's a large enough group of somebodies so that there's no consensus. The left-hand Shift key is located where it is because we wanted to have the character-typing keys inside the control keys. That means that the arrangement with the one extra key instead of being the Shift key with the character on the outside, is just the reverse. I have since gone back and looked at a lot of keyboards and found that a lot of them are just like ours— with one more key on the bottom. They may not have the same character in that position, but there is one more key along the bottom. It's not much of a problem in the long run. Fortunately, people adjust; in fact, if we were to change it now we would be in hot water.

Why are the function keys in two rows on the left rather than across the top?

We didn't want to put them across the top because we wanted to have a template there in case some applications needed a template across the top of the keyboard. That's the reason for that little ridge— to keep the template from falling down on the keys. The ridge is also there to use as a book prop.

Did you look at the international keyboard standards?

That's what's on the board; that's why there are symbols on the keys.

Is there anything different that you would do to the keyboard now that it's been out a while?

No. I'm not saying we would never come out with another keyboard that's different, but I don't have any regrets about the keyboard.

Are you familiar with the mice that are creeping around in the world?

Yes. That's a perfect example of the kind of experimentation that you would expect to go on.

Have you ever used a mouse?

Yes.

Do you like it?

It was just another way to do things. It didn't strike me one way or another.

Are you comfortable with the keyboard?

Yes. More than two million personal computers [from all suppliers] were shipped in the United States last year. Predictions for the future are more grandiose. They must not be very hard to use. When you look at the age levels of people using the machine— both the very young and the very old— and when you look at the backgrounds of the individuals, you have to conclude that the computers must be pretty darn easy to use, or else you would never have gotten that far.

Can we talk about specific software?

Sure, as long as it's ours.

The biggest software change that's happening is the upgrade to the 2.0 version of DOS; are there delays in shipment of the product?

Initially, yes.

Why is there a delay?

We guessed wrong on how many people would order the PC from day one. We thought there would be less demand than there is, so we had to catch up, and we passed that point.

Some people are complaining that there are problems with the 2.0 version and incompatibilities with the previous 1.1 version. Do you see that as a major problem?

There are some differences in the products, most notably in memory utilization. The 2.0 product is larger. If you had a program that barely fit in 64K bytes with version 1.1, it's almost certain that it doesn't fit if you move the program to 2.0. We haven't heard any significant unhappiness with customers or with the software suppliers, and that level of incompatibility is one that's understandable as you enrich your product.

Will IBM sell 1.1 indefinitely?

I won't speculate about our plans, but it's not a good idea to mistreat customers. We will do what our customers need us to do. If that means keeping 1.1, we will do it. If all the customers move to 2.0, it will be uneconomical to keep 1.1, but I don't know which way it will go.

We understand that Microsoft had developed something called the user shell interface for MS-DOS 2.0, and we don't seem to have that in IBM's 2.0. We have a command-prompt line that is much the same as it was.

PC-DOS and MS-DOS are two different products; you can buy either one.

Is IBM happy using the command-line scheme of having people type things in?

Microsoft has helped us enormously with PC-DOS, but it's our product. Microsoft has its own product. Although they are very similar— and I'm not trying to telegraph anything—I don't know how they're going to be in the future. All I can tell you is that our product works, it's fairly simple, and we're happy with it.

Are you satisfied with the language compilers and interpreters that are available for the IBM PC?

If you're talking about the ones under the IBM logo, we've had very good response, and we're pleased with everything except the FORTRAN compiler. The performance of the FORTRAN compiler is not what we think it ought to be. We've told our customers that we're trying to work on the problems. Whether or not we can do anything about them remains to be learned, although there are a tremendous number of satisfied FORTRAN compiler users.

As greater amounts of memory become more common, do you foresee that another version of a BASIC interpreter will allow easier use of all that memory than the current BASIC interpreter does?

I don't know whether we'll do that or not. It was obvious from day one that the machine had more memory than the Microsoft BASIC interpreter could use. We decided not to change the interpreter right from the beginning. I think it's been a good decision. The BASIC interpreter is essentially bug-free. To go back in and make it handle bigger address spaces would essentially mean a rewrite that would expose us to introducing error into the code. That flies in the face of the novice user's learning the BASIC language for something very simple. We traded quality for the additional capacity of the interpreter. I would make that same choice today. I think of the BASIC interpreter as an answer to a lot of things except big, complicated programs. If you need a lot of address space to solve the application, you should use languages that are designed for those kinds of problems. It doesn't bother me that BASIC handles programs that fit into only 64K bytes. We have moved the code— service routines and operating systems— out of the 64K-byte user-program space into the other address spaces so that the use of 64K is more efficient.

Are there any gaps in the lineup of software that IBM offers for the machine that make you uncomfortable?

No, because we went into this with the idea that we can't do everything. We tried to create a machine, some software offerings, and a set of business practices that made it easy for others to participate.

Are you happy with Easywriter 1.1?

Yes, I like it. People seem to like it.

Have you used it yourself?

Yes. I also tried to use Easywriter 1.0 and had the same experience everybody else had. There is almost no product [that runs] on the machine that we have produced that I haven't used.

Have you backed up the contents of a hard-disk drive? Are you satisfied with that procedure?

Let's go back to the 5 1/4-inch disk discussion. You can put only so many bytes on a 5 1/4-inch disk, and that introduces some disk handling. I don't have any other way to do it.

Do you think the industry will eventually solve the problem?

I don't know that it's a problem. When the machine first came out, people asked, "Aren't you upset that there is more memory than there is disk capacity on the machine so you can't dump your memory to disk?" The answer is no. It has never been a problem. It's a theoretical problem. If you insist that you must read the entire contents of your file when you do a backup, there will be a delay in handling disks, but people are smarter than that. They don't dump the entire contents of their file; they only dump the stuff they're really concerned about. Most applications build transaction files; they have to dump only transactions. If they take the time to recreate the file, they'd have a problem.

It's my understanding that the PC and the PC XT have recently been introduced in Europe and elsewhere overseas. Do you think that IBM will be coming out with some software packages that will be specifically for the international market?

I don't want to speculate on that.

Why did it take so long to bring out the Intel 8087 coprocessor?

We wanted it to work.

Are you saying there were troubles with it?

Sure.

Is that why you now get a matched set of an 8088 and an 8087?

The newer 8088s have slightly different characteristics that result in better performance of the 8087 coprocessor. By shipping both processors we know the customer will get the best possible performance from the 8087.

Do you foresee the extra power that you now get with the 8087 being an extra selling point, or do you think that the casual user won't care?

I think for the casual user to feel the effects of the power of that device, some support and programming would be required to be available on the machine that are not there today. The people who are going to get it and benefit from it are the people who will write programs with the device in mind, and there are a lot of people like that, but I don't think it's the general population.

So you see that as being kind of an extra turbocharger that the drag-racing set will like?

Yes, the ones who'll need it will love it.

Sometimes IBM makes product changes that some people can't see the reasons for. Why has IBM stopped doing knock-out panels in the back of the machine?

Because they produced quality problems, and we wanted to produce a machine with no defects. They fell out during shipping and handling.

So it was a shipping annoyance?

A defect is a defect— it doesn't matter if it's a corner crushing on the cardboard box you ship it in or the machine not functioning at all. It's exactly the same for all defects. And when you start out with that mentality if you have a defect, you ask not only how to fix it but also what is the source of this problem, and how do we eliminate the source? In that particular situation we eliminated it by not having it. We couldn't sense that there were a lot of people who needed it.

Back to the design of the case. Did you consider trying to go for a smaller footprint for the machine, possibly by trying things like stacking the motherboard on top of the disk drive?

It was the smallest footprint we could figure out. We wanted to have the machine work in a wide range of environments: heat, temperature, humidity, and electrical interference. When you start considering all this, you can't make it as small as you would physically make it because of the electrical characteristics. We have what we think is a balance. The more closely you put it together, the more difficult it is for somebody to add something to it; you get hard-to-manage mechanical assemblies. That makes putting it together and taking it apart hard and error-prone, or you create fittings that are not generally available, so other people can't get the equipment they need to build an add-on piece of hardware.

You've talked a lot about designing the machine to make it easy for people to use— to experiment with the machine, to add to it. Were you thinking more of dealers than experimenters or hobbyists?

First, we knew that dealers would have to provide warranty service. We tried to design the machine mechanically and electrically so that it was simple to understand and work with. We chose electronic components so that there would be commonly available parts, with the serviceman at the bench in the store in mind. Our goal was to make the machine as easy for him to use as for a customer, because he's a customer too. If we burden him with high-technology complexities-tools and equipment that are unfamiliar, hard to get, or expensive, parts that are in limited supply or available only from IBM— these things would make the machine difficult to service.

The new IBM color monitor is certainly appreciated, but are you satisfied with the display quality you get with the color display adapter?

Yes. I think it's a good balance between price and function.

Did you consider making a special color monitor that used higher frequencies?

Yes, but then you have to buy more memory that fits on the color adapter card. It raises the price. We think the granularity, number of colors, and number of memory bits on the card strike a good balance between definition, function, and price.

Do you think we will be seeing more applications that use graphics— that graphics will be a dominant segment of the market?

Yes. I think the old saying that a picture is worth a thousand words is true.

Do you see color as a practical tool now in business graphics, or simply a nice feature to have?

I think that color is going to change over the next short period— maybe a couple of years— from being something we think about as an interesting curiosity to something we won't know how to get along without. It will be that dramatic a change. Look at color TV. You're using more senses, and it's probably well proven that the more senses you involve, the more likely you'll get the message through. If you don't think color is important, turn it off the next time you watch a football game and see how you like it. It's a feature that is going to quickly find use in all applications, not just in business.

Were you disappointed that so many users were not getting the color display adapter for a while?

I wouldn't say that so many were not getting it.

There was a study that said 90 percent of the people were using just the monochrome display.

I'm not going to comment on somebody else's study. I know how many are buying it.

Most IBM software seems to allow users to make a limited number of copies. Do you have any thoughts about copy protection?

Do I ever. It's wrong to copy-protect programs. The only reason anybody does it is because there are thieves who steal your product. That's wrong, too. There ought to be some way to stop that without creating products that are unusable.

What do you think of having serial numbers in the hardware match to the software?

None of those techniques work. There is no one who has a technique for protecting against copying code that works in all environments— hard disks, communications, local-area networks, single-user, easy-to-use, or hard-to-use. I guarantee that whatever scheme you come up with will take less time to break than to think of it. I think theft is also a threat to software development. It's going to dry up the software. It's incredibly difficult to write software, and people are going to stop doing it if they can't get a legitimate return for their efforts.

Are you satisfied with the market success of operating systems other than PC-DOS— CP/M-86 and the UCSD Pascal p-System?

We came out with three operating systems because we couldn't figure out where the propensity would be; we wanted customers to decide that.

Why were CP/M-86 and UCSD Pascal so much more expensive than PC-DOS?

You'd have to talk to Softech Microsystems, which did the research.

Was the price determined by Softech Microsystems' licensing agreements with you?

Yes.

What do you think about Digital Research's recent moves to cut the price?

You'd have to talk to them.

Have you looked at any of the up-and-coming languages, such as Logo?

We've announced Logo for our machine, to be available in the fourth quarter.

Do you think that's a good package?

I think it's terrific. What we have on our machine is really dazzling. It's been a lot of fun to experiment while we were developing it. I don't know how to project its popularity, but I've had a lot of fun with it.

Why did you decide to put Logo on the machine?

Because people in the education industry said they needed it.

Have you used it yourself?

I use everything we're producing.

Do you have a machine in your office and at home?

Yes, to both. I prepare letters at home. I have some bookkeeping information. We have a few investments that I like to pretend I can manage. I play games. I use it as a way to see every package we're developing and planning to introduce.

Do you use non-IBM software?

All the time.

Do you care to say which?

No, but I get my hands on as much of it as I can and see what it looks like.

Do you think other people are developing good software?

Absolutely. They sure are.

Are you pleased that a certain subculture is growing up around your machine?

I love it. I think we're in an era in which the public has adopted personal computing in the same way it adopted the automobile. People want to know everything they can about it. That era will probably pass, but that curiosity is almost sensational right now, and I think it's good.

Can we expect to see the same kind of shakeout that happened in automobiles?

Logic tells you that it has to happen. But logic also predicted the industry wouldn't sell one and a half million personal computers until 1985, and the industry surpassed that last year. So who knows what's going to happen?

Has IBM been surprised at the success of the PC?

I think the world's been surprised by the success, but not just about the IBM machine; I'm talking about personal computing as a phenomenon. All the industry reports you could find in 1980 projected one and a half million in unit sales [of personal computers] in 1985. You could have called Future Computing or Dataquest or anyone else and they would have told you much the same thing. We don't have a crystal ball that is better calibrated than anybody else's.

It seems that you have the same problem — forecasting— that most people have in this explosive market; it's an imprecise art.

It's not that you can't predict what will happen in those areas that you understand. The problem lies in the very thing that makes this product family popular— its application to completely unknown uses. That's exciting, but it's also the very thing that makes the business totally unpredictable. [See "The Perils of Forecasting."]

Are customers for larger IBM computers moving to buy PCs as well?

They're doing it in great numbers.

Will that fundamentally change anything in your relationship with those customers?

I think we're providing them with the solution that they want, and that's what they expect of IBM, so I don't think that's a fundamental change.

Is the existence of so many distributed personal computers going to change data processing as we know it?

No, but I think it will involve a lot of people who aren't now involved.

Can you characterize sales of the personal computer through different distribution channels?

I could, but I don't want to. That information is important to us in running our business, but not important to anyone else.

We have heard that some IBM direct-sales people inadvertently have undercut a dealer's price.

I think you could hear the other side just as easily. For every story you can tell me about a dealer feeling that he lost a sale to an IBM direct salesman, I can tell you about a salesman who thinks he lost a sale to a dealer, so we probably have it about right. I think there's another phenomenon that's new in this equation, and it may be particularly unique to IBM personal computers. Every other IBM product prior to the personal computer was available only through IBM salesmen. IBM customers were never faced with the question of support versus product because they both came via the same organization. Now the customer can distinguish support of the product. That's an adjustment that all of the distribution channels are going through. The customer now has to participate in a two-step decision: determining what product he wants and from whom to buy it.

We wouldn't be doing our jobs if we didn't ask about a "Peanut" machine or any extension to this product line.

Call the Wall Street Journal. They're the only ones I know of who have written about the Peanut.

How about "Popcorn?"

They've written about that, too. I think it's fascinating that they decided to get into product design.

Did they seem well informed?

I have no idea.

Well, we had to try.

Estridge finally alluded to the inevitability of follow-up products in summing up his thoughts about the IBM PC. He characterizes the PC as having enough horsepower and capacity to have a long life cycle: "It's an affordable product, there's a lot of software for it, it's easy to use, and it can be extended. I'm comfortable that it will be around for a long time, and it will probably be extended. It would be silly not to follow it up. More important, I think customers expect IBM to follow it up."

---

The Perils of Forecasting

IBM's Estridge explains how his division's forecasting procedure works in the following manner.

Each quarter, IBM asks everyone who is selling the PC, including IBM's direct sales force and dealers, for a projection of purchases for two periods: the next quarter and the three quarters following it. In October 1982, for example, the division asked customers how many systems they expected to buy for the period from January through March, 1983. "We're kind of asking for a commitment," Estridge says of the process, "although no contractual penalty is attached to it."

Then IBM asked these customers what they expect to buy for March through December, 1983. "We do that every single quarter by product. It's pretty boring, but we do it with all the people who sell our products," Estridge says.

When customers returned in January of this year, ostensibly to talk about their system needs for April 1983 and beyond, they wanted to talk about January through March all over again. They doubled their orders for that first quarter. "They told us that they'd given us the wrong numbers, and the numbers were low by a factor of two since October 1982," Estridge says.

"Then the same darn thing happened again in March, when we were supposed to be talking about July through September. We can only handle so many factors of two" Estridge says. "We've upped our production rate three times this year; production is very high. We're extremely pleased that we can build a quality product at that rate, but it's not enough. The demand is increasing at a very fast rate, and we're doing everything we can to stay with that demand. But if the demand keeps on going at these rates," Estridge warns, "at some point there won't be any more parts. We're not there yet, but we can see where it is from here."

Human Factors in the IBM PC

The placement of certain keys in the keyboard of the IBM PC has been widely criticized, but Philip D. Estridge cites prior IBM experience in building typewriters as being helpful in designing the PC keyboard. He points out further that various human-factors considerations are reflected in the overall PC design that he says make the machine comfortable to use.

The keyboard can be tilted, for example, to assume a flat-surface angle or a tiltedup angle. Estridge says both are standard angles that make users feel comfortable. "We don't know why people feel comfortable with one of those two angles," Estridge says, "but we've learned from building typewriters that these are the two popular angles for wrists."

He also cites studies of eye-pupil dilation that influenced the PC's design. He says these studies have shown that there's a direct relationship between pupil dilation and fatigue; the more a user's pupil dilates, the more fatigued he may become.

"If you can cut down on contrast changes as people use the equipment, you reduce the likelihood of frequent pupil dilation."

How has that principle been applied to the IBM PC? Estridge explains it this way: "Imagine that the center of the machine is a high-contrast area and the outside of the machine— the background— is a low-contrast area. The machine has grades of contrast as you move from the screen outward. Its highest contrast is on the display tube. Immediately around the tube is a lower-contrast border, and then the cabinet curls round to form an even lower-contrast frame.

"The eye then progresses from seeing dark gray to light gray to medium white, and, beyond that, essentially a noise background. As the eye moves across those boundaries, it doesn't experience much contrast change, and the viewer doesn't get tired."

What computer ads would you like to see in the future? Please comment below. If you enjoyed it, please share it with your friends and relatives. Thank you.