MicroTimes' Interview with Doug and Larry Michels from Santa Cruz Operation (1987)

They talk about XENIX and more.

from the February 1987 issue of MicroTimes magazine

The Santa Cruz: Taking Care of Business With XENIX

by Bennet Falk and Mary Eisenhart

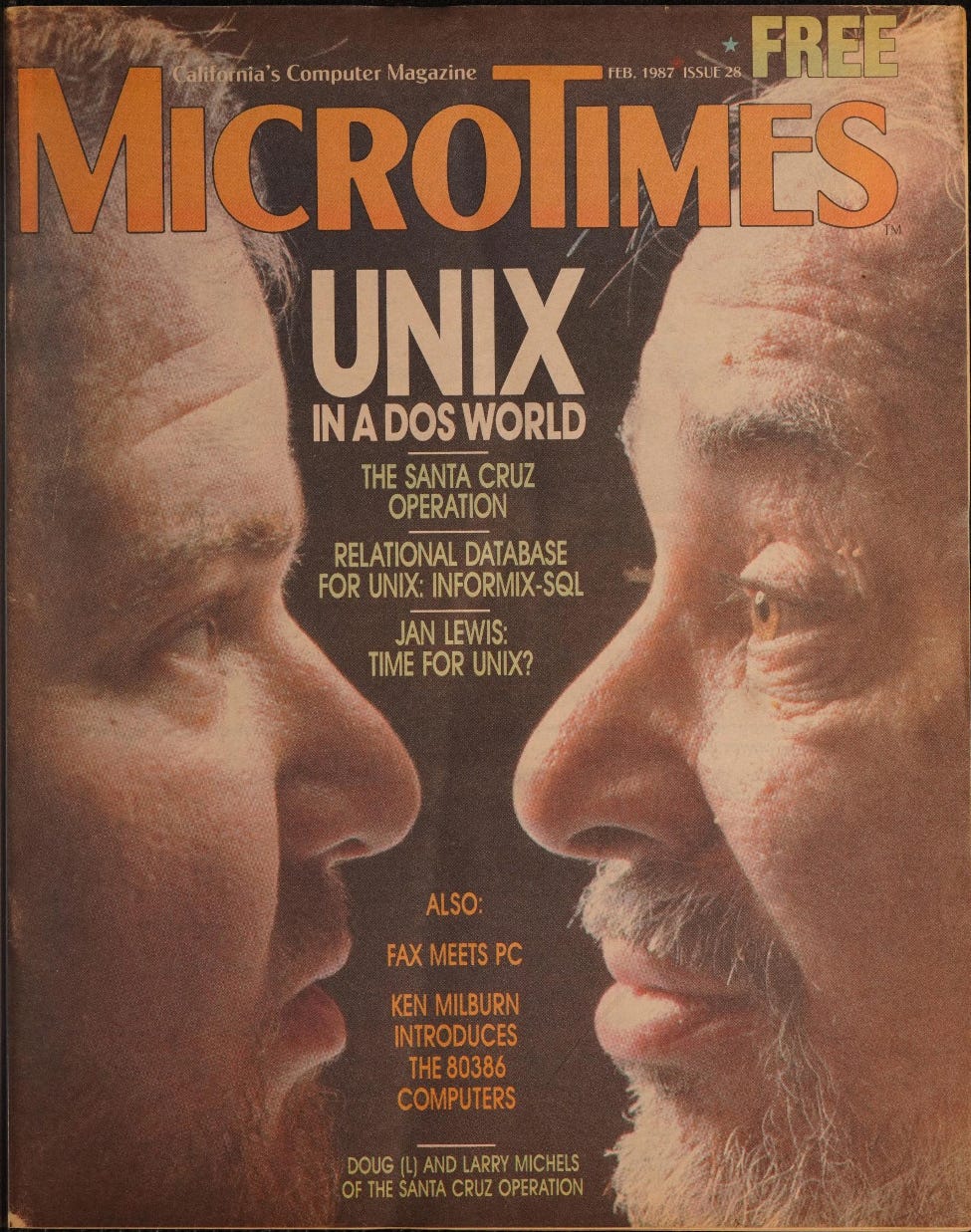

Photos by Marc Franklin

1987 may well be the year in which AT&T’s UNIX operating system comes into its own in the corporate work environment. An increasing number of businesses are discovering the merits of multi-user systems in which resources are shared among a number of PC workstations. Further, as fast, powerful machines based on the 80386 microprocessor chip become readily available, the absence of an MS-DOS that begins to tap the chip’s power makes UNIX an attractive alternative. Another significant advantage of this multi-user, multi-tasking operating system is that it’s relatively hardware-independent and runs on a wide variety of micro- and minicomputers, thereby protecting a company’s software investment as it upgrades to new generations of equipment.

The predominant UNIX in the business world is XENIX, a value-added version licensed from AT&T by Microsoft. Versions exist for many computers, most notably the IBM PC/XT/AT and compatibles.

In order to market XENIX effectively, Microsoft devised the concept of “alternate sources” for XENIX, by which smaller companies would join forces with Microsoft, continuing development of the operating system itself and of the application packages which would provide specific solutions. These companies would also provide all-important support services to users of XENIX-based products. There were two such companies worldwide: Logica, based in London, and the Santa Cruz Operation, based Cruz, California. In November 1986, SCO and Logica joined forces in SCO Limited, creating a unified alternate source for XENIX worldwide.

Founded in 1978 by Larry Michels and his son Doug as a consulting firm, SCO has been developing and marketing systems software for the UNIX environment since 1979. It offers a full range of support services and software packages for business environments. SCO’s software offerings include SCO XENIX System V, a commercially enhanced version of the UNIX System V licensed from AT&T; Lyrix, a user-configurable word processing system; SCO-Professional, a UNIX/XENIX based Lotus 1-2-3 workalike; SCO FoxBASE and FoxBASE Plus, workalikes for dBASE II and dBASE III; SCO UniPATH SNA-3270, mainframe communications gateways which allow XENIX systems to operate on IBM SNA networks; SCO XENIX-Net, a Local Area Network system for integrating XENIX/DOS environments, and a wide range of other applications.

With its extensive repertoire of products and services, SCO seems ideally positioned to take advantage of the arrival of new, powerful microcomputers to broaden the acceptance of UNIX in the corporate world. Meanwhile, however, new contenders are eyeing this lucrative market and. coming out with their own licensed versions of UNIX—the notable example being Microport, which offers a two-user bare-bones PC-based UNIX operating system for a mere $169, a package some manufacturers are bundling with their 386 machines.

When we visited the SCO offices recently, the senior and junior Michels (who now hold the titles of president and vice president of research and development respectively) spoke about SCO, its role in the marketplace, and how it plans to face future challenges.

How did you come to start SCO?

Larry Michels: The business started after a number of years I spent at TRW. I watched them struggle with how to move from a low technology company—auto parts, things like that—to a high technology business. The fact is, they bought some large number of companies, and failed with each one they bought.

There were a number of reasons. One was that the culture would only accept certain kinds of people. They weren’t willing to change to the people that they had to. Nor were they willing to change the management practices they had. Nor were they willing to change the budget or any other cycles that they had.

These were all high-tech businesses—point-of-sale, bank teller machines, credit authorization machines. One other aspect that TRW didn’t understand was that these businesses were computer businesses. They were software businesses. They thought they were buying a telephony business, they thought that telephony was telephony, but they really were computers. Unless you approached them as being computer businesses, you didn’t end up with anything.

Characteristic of the telephone business over a long period of time is that telephones don’t change fast because tariffs don’t change. However, introduce electronics and you introduce the ability to change faster, and suddenly you find yourself in deregulated environments where tariffs are no longer an issue. Speed was important, and yet the whole structure of the. business did not allow for speed. Fundamentally they failed because they could not understand the cultures they were going into.

Well, Doug and I took that here, and we thought, if TRW was having so much trouble, it was probably an interesting business, being able to offer what we had learned in how you go about making these transitions. And so we hung up a shingle and started to offer these services. We found out almost immediately that it was a futile business. Why? Because invariably the price of success was new management techniques and new management. And so the people that hired you, you had to go back to them and say “the way you succeed is change your staffing, change your approach, change your goals, change your methods.” And they said “Thank you,” and you were never invited back a second time. (laughs)

You cannot run a consulting business by doing that. So we recognized that working with companies and helping them recognize the disasters they were headed for was almost immaterial.

We had realized, from some of the work we had done, the value of portability—that you had to have the freedom to move through generations of technology without destroying the investment you had made in software. We began to recognize that UNIX, which we had used as a tool internally, was probably the coming vehicle. We also recognized the tremendous opportunity, because AT&T had this operating system and didn’t quite understand what to do with it. This was about 1981.

System 7 was the first UNIX licensing introduced with the ability to sell inexpensive binary licenses. Prior to that all you could do was buy source licenses, so the price of the machines was many thousands of dollars.

This was a tremendous buy. This was tremendous power. You could take inexpensive PDP-11 machines, put UNIX on them, and just about run circles around anything that was out there. We recognized that that was an emerging market, and that that was probably a place to invest and to start building talent. And then along came Microsoft.

Microsoft did something fairly bold. They said “Here is an enormous opportunity” —again, because AT&T was really not producing a commercial product. Microsoft’s grand plan was to take every major microprocessor and make a value-added form of UNIX called XENIX available for it. Microsoft, however, ran into an immediate problem. They were not set up to deliver support and hand-holding. They are in a business that’s largely based on being a commodity supplier—here is the product, pay us the money, then go off and make it work.

Not the kind of thing you can do with a UNIX operating system.

Not and succeed, anyway. (laughs) So they in effect hatched the idea— and it was a very good idea—the idea of the second source. They would set up x number of small companies that would, in effect, provide the kind of support and service that the larger companies needed. They set up a revenue-sharing basis so these companies would get a piece of the action, so to speak.

What finally happened is that there turned out to be two second sources. There was a company in England called Logica, and a company in the states called SCO. The company in England is the one we just merged with, and plan to use that to expand our capabilities.

SCO is a very unique organization. It is tuned to bring a high degree of value-added to the multi-user market. The high-end PCs—the 286 machines—are practically a revolutionary concept. They are metaphors, if you will, the same kind of metaphor that the Model T Ford was. The Model T Ford came along as not the pioneer of automobiles but the pioneer of transportation. Suddenly we had a low-cost, reliable transportation device for the masses. We didn’t have to live next to where we worked, we built garages, roads, planned our cities differently, and the world changed around us.

If you start thinking of the PC in a similar vein, that it is a very high power, low-cost, reliable source of computing power; if you put to it the kind of tools that SCO is pushing, namely the operating system and the various applications, tools that we’re adding to it, and turn that loose with people who can adapt these systems to meet the ordinary needs of business—the needs to communicate, the needs to gather data, present data, where you have a group of people that have to work together and share resources or report to a mainframe or another large computer someplace—suddenly you can do this for sums of money around $10,000. You don’t need a special environment, you don’t need an expensive service contract.

You don’t need to be locked into IBM’s way of doing things...

You don’t need to be locked into anybody’s way of doing things. You have the freedom to evolve the technology. In the same way that new cameras use existing films, new machines will be using the existing base of software. And the repercussions of that on society are going to be enormous.

The present computer industry is not established to deliver that kind of capability. Distribution houses tend to be largely storage, where they turn over software, they turn over hardware. A company like SCO has the resources, the engineering, the support, the commitment to take these products, work with the various Value Added Resellers and system developers to produce low-cost, reliable multi-user systems. It’s a whole new concept.

The English acquisition is so important because it fits the same pattern. The intent was not to set up an English subsidiary. The intent was to extend the types of services we were able to offer here on an international basis, to the multinationals, to people who care about how products move across world boundaries.

Obviously you expect that there’ll be a pretty large base of high-end PCs in Europe.

Step back and take a look at the PC market. At no time are we trying to say that multi-user systems will dominate this market. A year ago most pundits thought that if the market ever got as high as 10% UNIX, that that would be masterful. The fact is, on the high end of the machines, the numbers are way over 10%. I think at the most, though, we’re talking about markets that are maybe 20-25% at best. There’s maybe three DOS machines for every one of these machines.

The people that are moving machines in these markets—certainly ITT—are being very successful. The high-end machines are moving in Europe. Apricot has a 286 machine. Olivetti will have a 286 machine. I think we’re going to see more and more.

Doug Michels: The thing about Europe is that the market has different players. The only US players other than IBM that are really strong worldwide are people like ITT, H-P, NCR, and they’re all very strong on XENIX. One of the reasons is that the demand for XENIX is stronger outside the US.

Why?

DM: It’s somewhat historical. The international market is really more adventurous. Common wisdom is that Europe is one to three years behind the US, and they typically are. The AT stuff is hitting its stride now, rather than two years ago. But in terms of the Value Added Reseller component of the market, they’re more adventurous.

The reason is that they don’t buy the IBM answer as the only answer. The saying in the US is “nobody ever got fired for picking IBM.” That’s not a saying in Europe.

Leonard Tramiel at Atari says that “nobody ever got fired for buying IBM” has never been translated into German, and Atari’s very happy about it...

DM: (laughs) He’s absolutely correct. In Europe they worry a lot more about price/performance; they don’t spend money as freely on data processing. They were pushing multi-user CP/M systems. DRI was much more successful with Concurrent CP/M in Europe by an order of magnitude. In terms of the small multi-user system, Concurrent CP/M is the major competitor in Europe. XENIX is starting to be felt very strongly now, but those people tend to look for cost-effective solutions.

In Europe you’ll see very strong commitment by the independent software vendors to Oasis, Concurrent CP/M, all of those low-end, original multi-user systems. They all have strong followings and they’re still going strong. There are new machines being introduced this year with Concurrent CP/M as their operating system.

The loyalty isn’t to IBM, the loyalty of the end user is to the local VAR. The local VAR there is some guy who’s been around for 100 years; whether he was selling adding machines or whatever, that company has a reputation, and the local end users have the opinion that if they buy from this guy who’s been in their town for 100 years, he’s not going to let them down. He’s got too much at stake. They’d rather trust that guy than trust IBM to deliver them a solution that would be stood behind for years to come.

And it’s these guys, the local VARs, that are beginning to see XENIX as a vehicle for building cost-effective solutions. In the last six months we’ve seen International take off at something like twice the growth rate of every other market sector we’re in. We’re just seeing the tip of the iceberg.

Those guys are beginning to say “XENIX on a 286, in price, performance, reliability and everything else, is the best solution we can find right now.” They’ll buy the Olivetti or the Apricot or the H-P or whatever 286 box, and get XENIX on it and get the software and deliver it tothe end user. That’s going to be a solution that’s solid, that’s going to be around for years to come, it’s going to be somewhat hardware-independent.

We think it’s a market that doesn’t go away easily. They’ve got a history of loyalty, a history of taking longer to make the decision and then really committing to it and investing in it.

LM: It’s not only Europe—Australia and New Zealand are also very high penetration. We haven’t seen much from the Far East.

DM: South America’s beginning to go. The funny thing is, it’s really country by country. In the smaller countries, there’s really only one or two key VARs, and they were DEC for for awhile, then they were Data General for awhile, and then they got into CP/M and Oasis, and what happens in each country is that they gradually realize about XENIX. Then they realize that SCO is the right place to get the XENIX. So we’ve just had this big explosion in Venezuela...because somehow the message got out! (laughs) Because somebody customized the word processor and did the things to make it acceptable in that market.

Do you sell directly to end users or operate exclusively through your dealer channel?

DM: We do sell direct to end users. We sell at list price directly to end users. We try not to compete with our dealers, so we don’t discount, we don’t do anything to attract that business, but we take it. We always tell them, hey, there’s a dealer near you. But it’s still a young market; the dealer coverage is getting pretty good now, but when we started it wasn’t. So if somebody calls up with an American Express card and wants to buy something, we’ll sell it.

Do you offer support directly to end users, or do you usually work through your dealers?

DM: In the US, we don’t expect a dealer or one of the smaller VARs to fully support all of our products. Every one of our boxes in the United States goes out with a 30-day hotline warranty, an 800 number to the end user. And it’s fairly inexpensive to continue that as a BEOeuEaOe service.

In Europe we do expect that the dealers and distributors are capable of providing end user support. Because of the language and time zones, we always try to work through the dealers in the rest of the world.

In the US we talk to a substantial number of individuals, and that’s good because it feeds back directly into our organization. Every release we think “What were the ten most expensive things to support in the release before?” We have this incredible vested interest in making those ten things either go away or be easier to support.

Installations are a huge percentage. In the early days we made it too hard. The PC market is an awesome thing—these machines that are supposed to be clones are really only almost-clones. We’ve learned the hard way that clones aren’t clones, every one of them has its own thing. So now if there’s anything we can do to make a product adapt itself, we’ll do it.

One of the amazing things that we’ve accomplished with XENIX is that at this point you take it out of the box and load it onto anything that vaguely resembles an AT, and it just sort of gloms in there and pokes around and says, oh yeah, that’s a Hercules monitor and an Arkive tape drive, and when you boot up XENIX it comes up and it says, you’ve got a Hercules monitor and an Arkive tape drive and a parallel port and two serial ports and eight megabytes of memory .

LM: The investment just keeps adding to it. It’s one of the nice things about the market, because you can pioneer the market, develop the market, and get the benefits. It becomes very difficult for somebody else to try and jump in.

Between development work, the operating system, the communication level, the human interface level, the database level—it’s a hell of a team that makes this all work. That’s why the UK acquisition was so beautiful, because it gave us the only remaining capability out there that could have fit like a glove.

Do you develop all your software in-house?

LM: We use combinations. Some of it’s developed in-house, some of it is team developed. More and more software developers are understanding that they can’t outreach this market. It’s sort of like being the producer of the show and the best way to get marketing is to go to CBS. So you often get the opportunity of picking up products.

The question then is, does the product meet our own requirements, does it do what we want it to do? It generally takes further investment on our part. The product we deliver has the flavor and look of an SCO product. Very often we do the documentation for it, the handbooks and user manuals.

How is the XENIX product itself continuing its development? Is most of the work going on here or at Microsoft?

DM: We’ve been doing joint development on XENIX with Microsoft since the very first version of XENIX on the PDP-11 five years ago. Over the history of XENIX we’ve probably done 50% of all the work. If you combine what we’ve done and what the group we’ve acquired in England has done, it’s probably higher than that.

We build the product we ship. We give whatever we did back to Microsoft, and it generally ends up in the next major XENIX release.

How do you decide what you need to develop?

DM: We talk to our support team, we talk to our VARs, we talk to our OEM sales department, we hold lots of meetings and write lots of specs. We’re on the verge of releasing a fairly major release in January; it’s got a heavy emphasis on international features like the 8-bit character sets. It’s got a heavy emphasis on supporting some new devices— there’s a big push for tape devices which were never officially supported before. The 150 megabyte disk floppies are really difficult media to do daily backups on. So the market said, we want tape, and we said, ok, it’s getting too confusing, there’s too many vendors out there with dissimilar tape drivers, so let’s-standardize that.

So it’s really an iterative process. Every release we make a long list of the things we’d like to do, then we prioritize it and decide how long we’ve got till we’re going to put out the next release and how far down the list we can get. But the first thing on the list is always “What is causing the users the most trouble? Where is the support dollar going?” Because unlike most companies, we talk to the end users. It’s an immediate payback—if we solve a problem, if we cut down one phone call per user, that’s a huge thing. So if it means improve the documentation, if it means improve the installation procedure, if it makes the product more automatic in recognizing the machine it was just poured into, then that’s all stuff we have to do.

LM: We also like to listen to the propositions that there is this enormous market here if the product had this one additional feature...(laughs) So we sometimes deal with the one additional feature.

As a matter of style, if we want XENIX to lead, and we want SCO to lead, there’s a strong concern about how you interface with the rest of the industry. We try to keep as open a door as we can to the independent hardware vendor, to help them interface their hardware to our products. Some is done for free, some is done for charge, it depends on the importance of the product and the amount of help that’s required.

The same thing is true of the independent software vendor, even to the extent of competitive products. There may be competitive applications out there, that they need help in interfacing to our operating system. And it’s perfectly legitimate, you just have to do that, it’s part of the game. The customer wants their product, but they still want our operating system. And so you have to step away from your own products, and offer that kind of freedom.

DM: Also, as we get into things like XENIX-Net, which is bringing together DOS and XENIX systems, there’s a lot of players. We have active relationships with Excelan, 3Com, etc., to make the various networking systems compatible with XENIX. We’re getting very good cooperation because the networking vendors realize that XENIX is important in the networking strategy. They realize that if SCO says that theirs is one of the five cards that works in a XENIX-DOS mixed environment, that’s good. And so they’re willing to send engineers over here to live with us and work cooperatively on making the product fit their architecture as well as ours.

We’ve had a lot of pressure from the federal market, which needs removable media for security reasons. We just announced at UNIX Expo a relationship with Iomega to support and actually deliver XENIX on a cartridge. You can buy a 20 megabyte cartridge which has XENIX pre-installed, you pop it in and you’re running XENIX. Iomega made special arrangements for us to get cartridges and duplicating equipment so that we could offer XENIX on a cartridge.

So we’re constantly working, listening, entertaining these propositions. The discussions with Iomega have gone on for a year and a half to finally get to the point of being able to ship a cartridge with XENIX.

So the cartridge would be installed in a regular DOS machine and you could just switch between operating systems?

DM: Sure. You put in a XENIX cartridge, you’re running XENIX. You put in a DOS cartridge and you’re running DOS. And if you want to take the thing and lock it in the vault, because it’s got secure data on it, you can take it to the vault and lock it—which is required by law on a lot of projects. It’s either lock the whole AT in the vault or lock the cartridge. So the cartridge looks like a good solution.

Are we likely to see XENIX on a CD-ROM anytime in the near future?

DM: I wouldn’t look to see XENIX on the ROM. I would look to see XENIX able to access the ROMs. I think that because of XENIX’s natural role as a server in a network, that if I want to put a gigabyte of online data available to 100 DOS machines and terminals and telephone lines, that the obvious place to stick that is on a XENIX box. I expect that we’ll see device drivers that talk to CD-ROMs.

There wouldn’t be any great advantage to putting XENIX on the ROM. The CD-ROMs are way too slow to run XENIX effectively. But to access the databases that will begin to be available, it makes perfect sense.

We’ve started to explore that. We went to the first CD-ROM conference, and we’re trying to understand where that’s going. But XENIX really needs read-write capability.

What kind of doors do you see the 386 machines opening for SCO?

LM: The focus that we see is really a focus of machines doing work. It isn’t a matter of moving in a machine to make an existing business easier to run, but rather designing businesses that work around these machines. And the 386 just gives you the power to do that. It allows the work group to be larger. It allows what the machine can do to be larger. It does it all, without adding any real cost to the system. You’re buying the workhorse; you’re buying, if you will, the horsepower to do a given task in a given work environment.

What we’re seeing is a move toward solution selling. You’re not selling the machine, youre selling a solution, the answer to a problem, be it communication or office productivity or the sharing of certain information or the flow of money or what have you. The 386 is simply that— more and more power. As the next generations come along, they just do more.

SCO once had a version of XENIX on the Lisa, on a 68000-based PC. Since both Amiga and Atari have entered the market with 68000-based machines and Apple’s beefed up the Macintosh line, do you think there’ll be much of a market for XENIX on these machines, or do you think it’ll stay primarily an Intel-oriented product?

LM: Clearly there will be a move back; I think there’ll be a move back even within Apple. The issue of the Atari and the other small 68000 machines being single-user is probably not real. I don’t see any reason at all why UNIX will not come in.

The question that really has to be answered is the difference in the market between the tinkerer-hobbyist and the business environment. Will people invest in putting business systems on those machines? Would there be any real advantage in putting them into office environments? The problem you have is that somebody has to take the investment we’ve made, then use that investment to make another investment to make these machines do the work. That could be the internal VAR in a large corporation, or the external VAR. The VAR has to be convinced that there’s a real advantage to doing so. The cost of the machine is not generally an overriding concern in the total investment.

In the past year we’ve seen a lot of price-cutting forms of UNIX. We’ve seen Microport come out as a rock-bottom cost UNIX system. Do you think that SCO would ever sell a product like Microport?

LM: You have to ask yourself, what is Microport selling? First, they’re not selling any heavy investment in the product, because the investment was made largely through the work that was done by DRI and funded largely by Intel and AT&T. They took the product and simply said, we have royalties on a product, we’ll take that product and move it out.

Because it’s an established market, because XENIX is the established product, they’ll do, in Microport’s own words, a Borland strategy. This is hard to compute. The Borland strategy was in a high-volume market that was clearly elastic. Cutting the price produced more volume. The Microport market appears to be the UNIX hacker, the UNIX guru who is willing to buy something cheap and doesn’t really much care about the value-added that SCO brings in with its applications. You clearly cannot support the infrastructure and R&D and all that the market is asking for on the price structure that Microport is using. Consequently, I think we’re seeing a hacker’s product.

When we first brought out the 8086 products, we were confronted by unrealistic pricing that IBM had done. They had priced the product at $395, which just wasn’t adequate to provide the margins you needed to being the product to market and at the same time fund the development work. Even at that point our wisdom said no price of $395 could support a viable business. And so our first product coming out against IBM was a $495 product.

DM: IBM eventually raised the price to $595.

LM: And even at $595, given the margins, given the royalties you have to pay AT&T for a product, and given the kinds of discounts that permeate the various chains, given the real cost of delivering the product, you’re just barely at the right price there.

Along comes a Microport, saying I’m going to do the same thing for $169—he’s got a mail-order product. He can’t support dealers, he can’t support advertising costs. There’s just no way you can build a business based on that and deliver a quality product. We’re supplying a major engineering department here, now 125 people. Somebody has to pay that bill. It has to come out of the products that we’re doing. And so it just doesn’t make any sense. I believe what we’re seeing is a philosophy that says if we didn’t price it cheap it wouldn’t sell; if we price it cheap itll sell, and that’ll give us time to figure out what to do.

DM: Even if you look at the products that Microport sells with its UNIX, the word processors, spreadsheets, databases that they’ve designed, they’re selling them at four times the price of the operating system. They’re operating off of an anomaly in the AT&T pricing that they were able to take advantage of, because — as they advertise—they’re the same people who used to work for DRI, who did the port. And so DRI paid them-to come up to speed, to learn the product, to do the port, with Intel and AT&T money. They’ve taken advantage of that, used the AT&T royalty structure, and are selling the thing at a very low margin.

That’s fine, but what happens when the 386 comes out and they’re not the guys who are doing the port for AT&T? They’ve got to take whatever the port is, learn it, adapt it, and do all that other stuff.

LM: Furthermore, if you look at the product they’re selling, it is not a comparable product. It is much less refined. It is really not a satisfactory multi-user product.

Is it correct that Microport has never been object-code compatible with XENIX?

DM: They did claim compatibility early on. They retracted that. That was an error in judgment. It’s technologically very difficult. It’s technologically practically impossible without proprietary knowledge. So there’s two questions. One is, is it worth the investment to do it, and two is, if they did it, given that some of their employees had proprietary knowledge, would that be a problem? And all in all, I think wisdom won over.

They acknowledged, I think quite rightly, that in order to sell the UNIX you’d have to have applications. The applications base is built around XENIX. We worked very hard to get the applications base built around XENIX. And therefore, from a strategy of competing with XENIX, XENIX binary compatibility was very important. It just turns out to be very expensive.

It also turns out that, as time changes, XENIX is evolving. So not only is it expensive once, it’s expensive for a long time. And so, even though from a marketing point of view it was a desirable goal, it wasn’t within the scope of what they could do.

The effect is that currently we’re not seeing MIcroport take away any significant amount of business away from us. If they’re getting other business, it’s business that couldn’t afford XENIX, wasn’t a customer for XENIX in the first place. I don’t know how much business they’re doing, but it doesn’t seem to be our business.

I suspect, if anything, that they might be doing us a lot of good, because if they take the people that aren’t willing to spend the money to buy XENIX in the first place, they may learn enough about UNIX to decide they want to go to a professional level. It’s a lot like Nikon cameras—do you want the professional-grade product, or do you want the stuff for the consumer?

It’s a concern, because it confuses the marketplace; it’s not really a concern because it’s impacting the marketplace.

The other side of that coin, and something that we are looking at, is that AT&T has made it somewhat more attractive to sell a version of UNIX restricted to two users, which is what Microport has done. They get part of their price differential by no R&D. They get part of their differential by no dealer discounting or limited dealer discounting. And they get part of their price differential by using the two-user license.

What we haven’t yet really determined, and we’re actively looking at, is whether there’s a market for two-user XENIX. It’s clear that the bulk of our market is people trying to build multi-user systems, and therefore the two-user product’s of no interest. On the other hand, if somebody simply needs to replace DOS with something that can address eight megabytes of memory properly, the two-user version might be appropriate. And so to the extent that we can identify a market for a two-user restricted version of XENIX, we may very well use the lower-priced AT&T structure to offer a lower-priced version of XENIX with that restriction.

Who should be using XENIX?

DM: We certainly don’t advocate that there’s a XENIX vs. DOS argument. There’s a huge percentage of people that DOS is exactly what they want, and they should never change. If what you need is a spreadsheet on your desk to replace the calculator that used to be on your desk and do a lot more for you, there’s no reason on earth that you should go buy XENIX. You should go buy a machine with however much memory you need, get DOS, get Lotus, and everybody’s happy. We have no claim on that market. Nor should we. DOS is a fine operating system if that’s goal.

If your goal is to run a four-user accounting department, then how do you do that with DOS? The answer is, well, you buy four PCs and a bunch of networking stuff and try to find some accounting software that can live in that environment. You find out that’s pretty hard to do, and if you look at the cost analysis, it’s two to three times more expensive at best, and clunky besides, and hard to maintain and build. So if what you wanted was that four-user accounting system, you’d be crazy not to buy XENIX.

The other example is in the two-user world, if somebody’s really running against the limitations of DOS—the fact that DOS is an 8086 operating system today, and you may very well need an eight-megabyte address space to run some particular program. Trying to do that with DOS and AboveBoards and all that is kind of difficult. And so you go get XENIX and you just use it as a single-user system, if you want, but it’s running the 286 as a 286.

That’s even more true when you jump into the 386, and you say hey, now I want paging and 32-bit addressing and all that stuff. DOS can’t use a 386 even as a 286. Even when you get whatever the next version of DOS is, whenever it is, it will use the 386 as a 286, and you still have to solve the problem of using a 386 as a 386.

So XENIX fits two niches. One is that it’s ahead of DOS by several generations at this point, in using the chips at their rated power. The 386 really is equivalent to a VAX in power, architecture and everything else, but not without an Spon system like XENIX.

And two is, a reasonable number of multi-user sites. Depending on whether you’re a 286 or a 386, the problem of up to 32 users is very effectively solved with XENIX, as opposed to multi-DOS systems around some sort of network solution.

Other people probably don’t belong in XENIX. We don’t claim more than a fair share of the marketplace...

Debunking The DOS Vs. UNIX Myth And Other Popular Fallacies

“There’s a few issues that I think of in terms of National Enquirer headlines,” remarks Bruce Steinberg, SCO’s director of marketing communications. “‘Who’s Going To Win The Battle Of DOS Vs. UNIX?’ ‘Who’s Going To-Win The Battle Of Multi-User Vs. LAN?’ ‘Who’s Going To Win The Battle Of Mainframe Vs. PC?’ It’s almost an editorial lead that says if there’s a winner there’s got to be a loser.

“There doesn’t have to be a loser if somebody wins. If somebody wins, somebody else wins too. That’s good negotiation, it’s good technology. The only thing that loses is inefficiency, low productivity. UNIX is not out to do in DOS. It’s there to work with it. XENIX and DOS have always coexisted. They have a common genealogy, they have a common vendor in Microsoft.”

It’s Steinberg’s appointed task to present SCO’s products and services to the business community. He’s the creator of the company’s visually arresting ads, with striking artwork showing XENIX rising over the earth or freeway signs pointing to UNIX Solutions. And he’s the first to point out that SCO is at least as much a philosophy as a product line. “The results of buying an operating system, and the results of buying into a long-term working relationship with a software vendor, are almost indeterminate up front. It’s an act of faith, and faith coupled with reason is what’s going to get over in the long run, in terms of working with people. We’ve always paid attention to support. You let people know that you’re aware— we know what you need, and now were going to provide it.”

Presenting the true effectiveness and versatility of SCO’s XENIX frequently involves debunking commonly-held myths and rivalries, then pointing out that it’s possible to enjoy the best of several worlds while getting the job done efficiently. “Multi-user and LAN is a Classic dichotomy,” he says. “You have to pick one or the other. You either have to go multiuser, and here’s all the good news and the bad news about that, or you’ve got to go networking, and here’s all the good news and the bad news about that. I say, wait a minute, no. With XENIX-Net, you don’t have to make that choice. You can have networking of multi-user systems and get the best of both without sacrificing the strengths of either.

“Same thing with PC and mainframe. Somebody comes up with the idea of an SNA 3270 PC—you can put PCs on desks and you can give them SNA protocol and they can talk to mainframes. We have this facility called reverse passthrough on our SNA product, where a mainframe administrator can make his mainframe look and act like a PC for the purpose of communicating with PCs. And conversely we have a programmatic interface on SNA that can make a PC look and act like a mainframe.” SCO has recently ported the Microsoft C compiler, SCO Professional (a XENIX-based 1-2-3 workalike) and the Lyrix word processor to the VAX environment— prompting Steinberg to coin the slogan “Take your VAX where no VAX has gone before...”

“Rather than say it’s Us Vs. Them, I look at it that we’re all in this together. Because it’s ridiculous— the definitions break down anyway. The 386 machine has the power that mainframes had a couple of years ago. Sitting on your desk—virtual memory, four-gigabyte linear address space—where do the definitions stop and start anymore? It’s all about computers— it’s all about bits and bytes.”

As the distinctions between machine types continues to blur, XENIX offers the significant advantage of being able to tap the increased power of the new micros far more effectively than any current version of DOS. “You can take 286 code and run it on a 386 machine straight out of the box and it’ll run three or four times faster. You can take a 386 machine, run 286 XENIX and 286 applications, and they’ll run three or four times faster. You can take a 386, run 286 XENIX on it, and compile the 286 applications for the 386, and run three times faster again. And if you take those 386 recompiled apps, and run them on a 386 kernel on a 386 machine, you’re talking 30 times faster. And we’ve guaranteed this upward compatibility so that you’ll always preserve your investment from where you’re coming from.”

However, says Steinberg, the primary issue is less a matter of one operating system being superior to the other than of their ability to work together to enhance productivity. He points out, for instance, that DOS-based vertical market applications will probably continue to dominate their particular arenas for some time to come, and the ability of XENIX to provide multiuser features without sacrificing DOS capability is a significant benefit. Then there’s the undeniable advantage that an entry-level PC system can evolve as a company’s needs change. “There’s a tenuous balance between the need for PCs to be perceived as DOS, so there’s an entry-level position, but also as a good XENIX machine, if you want that capability. If you’re enough on the leading edge to understand what XENIX can do for you, you have it primarily as a XENIX machine, but it’ll still run DOS programs.

“Particularly the 386 was just made for UNIX—it’s like an engine that’s so powerful that you’re not even beginning to open it up with DOS. It’s kind of like having a Lamborghini and going to the supermarket. Occasionally you have to go to the supermarket. You’d be in trouble if you had a car that stalled if you had to drive it under 70 miles an hour. A good car that does 170 should be able to get you across town.”

What computer ads would you like to see in the future? Please comment below. If you enjoyed it, please share it with your friends and relatives. Thank you.

Very interesting! I am still trying to figure out how they managed to port Xenix to Intel 8088 without an external memory management unit.