MicroTimes Interviews Apple Newton Devs (1993)

The Newton laid the groundwork for the I-devices.

from the September 20, 1993 issue of MicroTimes

Newton: Very Personal Computing

Pocket-Sized MessagePad Adapts To Its Users

By Mary Eisenhart

After roughly six years of brainstorms, false starts, paradigm shifts, and all-nighters, Apple’s long-awaited and much-ballyhooed Newton MessagePad debuted August 2 at Macworld Expo in Boston. The MessagePad is expected to be the first of many devices—envisioned in one promotional brochure as encompassing everything from wristwatch-sized data entry pads to refrigerator-mounted family message centers to classroom-sized digital whiteboards—which utilize the long-awaited and technologically advanced Newton technology.

The devices won't all come from Apple. In a major departure from its historic lock-up-the-crown-jewels strategy, Apple is encouraging outside hardware developers to license the technology and build their own Newtons. As all the available MessagePads were quickly snapped up at the rollout (by the time you read this, they should be available at dealers nationwide) some eager buyers found solace in Sharp’s version.

When the Macintosh was unveiled in 1984, it included bundled software (MacWrite and MacPaint) to showcase its unprecedented capabilities. In similar fashion, the MessagePad comes with built-in applications and communicionts tools. Its handwriting recognition, much of it the work of a Russian software house called Paragraph, recognizes both cursive and printed handwriting and “learns” the individual user’s idiosyncrasies (initial reports seemed to range from delight, usually among people with neat handwriting, to frustration, usually from people with messy handwriting). Information can be gathered, stored, and formatted in free-form fashion, with “ink” handwriting, printed text, and graphics in the same page; it can be organized in calendars, names files, and to-do lists. Using built-in infrared technology, it can even be “beamed” to other Newton or Sharp Wizard users in the same location.

It supports a wide range of industry-standard printers, fax machines, and modems, and, with the upcoming release of the Newton Connection Kits, can exchange data with Macintosh and Windows computers—indeed, with the Pro version of the kits, place and synchronize the data in appropriate desktop applications. And, with a host of outside products coming along in PCMCIA and other formats, it can quickly be configured as a highly specialized tool for the particular needs of each user.

Philip Ivanier, manager of the Developer Relations Group for PIE (Apple’s Personal Interactive Electronics division, which includes Newton), notes with satisfaction that the new platform is attracting great interest from software developers, from industry giants like Oracle to startups developing their first product, as well as in-house developers in large corporations, special-purpose system integrators, and ISVs. “We’ve worked with two hundred or so integrators and developers thus far, bringing them on campus and teaching them to write Newton applications. In a matter of six weeks or so we've seen in excess of thirty different applications being demoed at our intro, which is more new third-party applications being shown for a new platform at intro than had ever been shown before. Developers see this as a great opportunity—a new platform, new beginning, some new abilities to do some new things they’ve never been able to do before.”

Newton’s operating environment includes some novel features. All stored information is available to all Newton’s applications, suspended in what its designers call a “data soup,” allowing users quick and easy access to whatever's needed. Additionally, its “intelligent assistance” feature lets the machine learn its user’s work habits and anticipate frequently performed operations, so that the handwritten message “fax Bob” might bring up a listing of all the Bobs in the database and present the appropriate templates and menus for faxed messages.

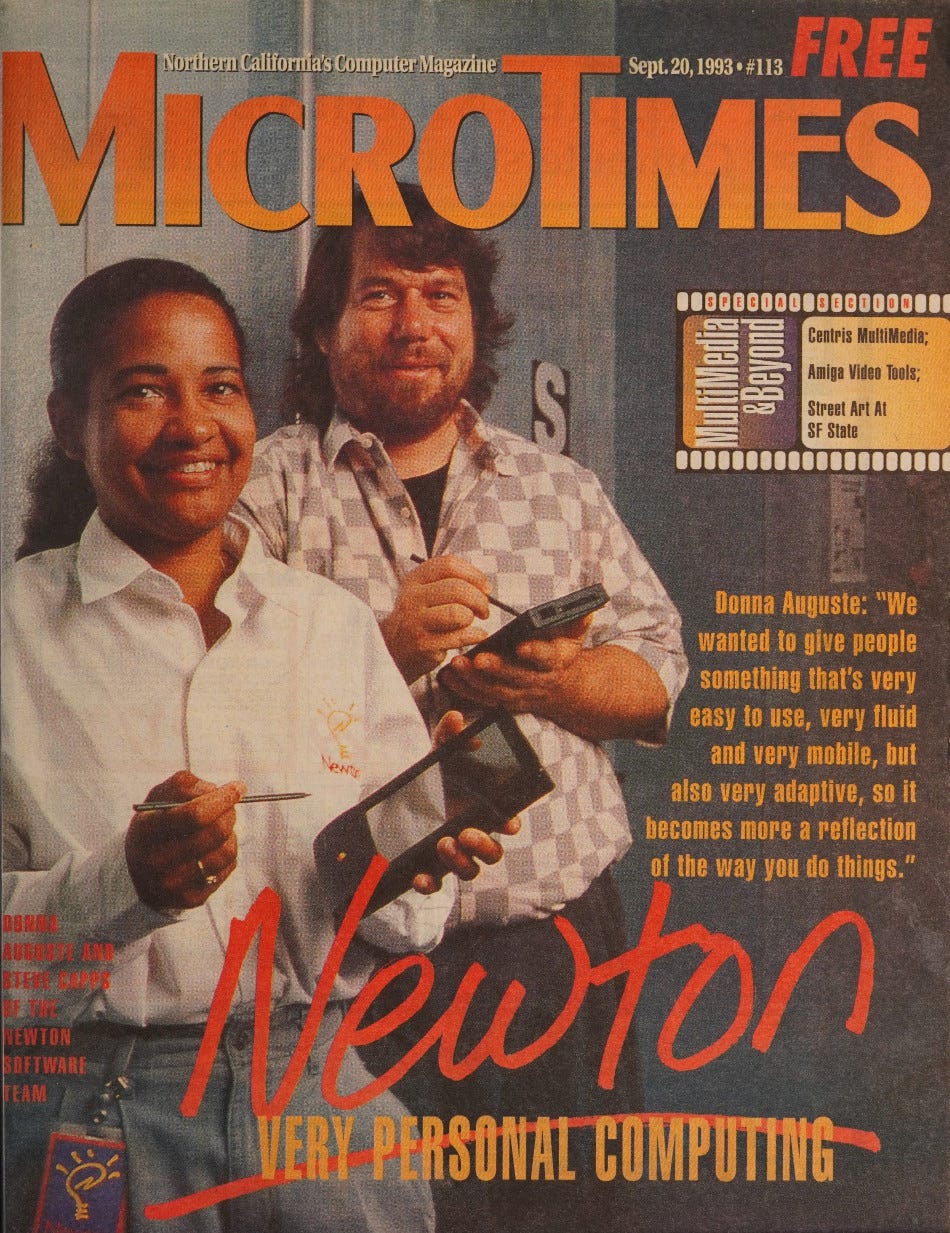

As the virtual dust from the rollout was settling, we visited Donna Auguste, manager of Newton Software, and software wizard Steve Capps (known to Mac veterans as the author of the original Finder) of the Advanced Products Group, in Apple’s new R&D center.

This is not a small, portable Macintosh; it’s a radically different thing. What were you trying to achieve—what did you think needed doing that couldn’t foreseeably be done with a Mac?

Donna Auguste: It’s a very different orientation. What we were trying to do was create something that was largely a communication device, and largely a helping device, or an assistant. In doing that, we wanted to give people something that’s very easy to use, very fluid and very mobile, so they could always have it with them if they choose to.

But also, very adaptive, so as you use it and spend time with it, it becomes more a reflection of the way that you do things of your own, the way that you communicate, the way you work on a day-to-day basis. This is a fundamentally unique perspective that we took from the start, in terms of the design of the system.

The technologies that had been investigated by some very talented people for along time just came into play as we tried to put the pieces together to accomplish that.

Where do the various bits of technology come from? The processor came from your joint venture with Acorn, and a lot of the handwriting recognition came from Paragraph...

Steve Capps: Pretty much the rest of it came from inside Apple. All along, if somebody outside or somebody in another part of Apple had some interesting technology, we'd talk to them. And obviously, from Apple people, we’d steal what we could, because there’s no sense not taking advantage of other people’s hard work.

There are many companies which shall go nameless that we’ve dealt with here and there, trying to take advantage of their stuff, but it didn’t work out. We weren't trying to invent everything here; Paragraph and a couple of other companies had some interesting handwriting technologies. We evaluated them, and Paragraph definitely came out the clear winner in terms of walk-up performance, so people could use it and not have to train it, not have to sit there and go through a lengthy process. It does get better with a person’s use, but it has great walkup performance, which is very important when somebody walks into a store and tries to use it.

We started this project with a clean sheet of paper. Starting from scratch was the hard part, and it took us many years to get enough critical mass on a piece of paper to ramp the other engineers up and get something we felt was a product.

At the stage where press first started seeing it, the ideas were already pretty jelled. The code obviously wasn’t. By doing lots of user tests, lots of experimentation, you refine it, rewrite stuff.

But most of what I’m talking about is what we saw before that stage, when we bit off more than we could chew, going down many false leads—all the good things that you do when you experiment. We have the scars from all that.

What you first saw with the press and what we finally shipped—conceptually it’s very, very similar. The product at that point had been pretty well defined—it just was a _mere_ question of implementing it. Which was very difficult.

When you take the mindset of just adding handwriting to an existing platform, like making a pen Mac or a pen Windows, you end up getting lost. “I do this with a mouse—how do I do the equivalent with a pen?” Or, what’s even worse, especially with Windows, “I do this with a keyboard”—because Windows is very strongly keyboard-based—“how do I do this with a pen?” You use Windows, you always have DOS lurking underneath it. You use Pen Windows, you always have keyboard-based Windows, mouse-based Windows, and DOS lurking underneath it, so you’re just adding more and more layers of an artificial syperstructure that you really don’t need.

There’s advantages of making a pen Windows or a pen Macintosh, but there’s a lot of baggage, both literal and emotional baggage, that we get by doing that. What's worse is your customers say, “I’ve got my Excel macros and I have to be able to run that; I have PageMaker and I'd die without PageMaker.” They don’t understand that PageMaker on a screen that’s 3 x 5 inches doesn’t make a lot of sense.

We kind of saw that movie with the Mac and the Apple II.

Yeah, exactly. “I can’t run my favorite Choplifter game that I ran on my Apple II.”

So anyway, by pushing reset we gained a lot of freedom there.

DA: One of the other things that’s different between this system and some other systems is that in the Newton system all the information is stored—users put their data in, data they want to be able to communicate, and give to other people, and add to, and enhance with information coming in from other people. You want to take it and put it into a relatively rich structure, as opposed to just a relatively flat structure.

With a rich structure in place, you have a lot of different applications that can access the same information. You don’t have to go and swap context and bring in another application with this data. You have a set of information with all the links and relationships in place, and lots of applications can see, with different viewpoints, that same set of information, and share.

By having put that structure in place with that information, and making it more like a knowledge representation as opposed to flat data, we can leverage it for things like Newton Intelligence.

Newton Intelligence is based on the notion that if the user has put some information in the system, and wants to act on it or do some action that takes advantage of it, we’ll try to understand or guess as much as we can about that action or that task.

For example...

SC: Say you had a group of people you worked with, and had messages like “eat at 3.” You sit down at a Newton today, and you want to write a very short message. My message is “Meet me.”

So I write “Bob,” and it says, “I understand what ‘Bob’ is”—it kicks in the intelligence, it looks up all the Bobs I know, it gives me a choice of the Bobs. So I can pick the Bob, and then I say, “send the message.”

When I wrote my application, I didn’t have to worry about how to store names, where to put this information. In fact I didn’t even have to program this thing—this is all built in. To write this application, all I had to do was take an existent piece of the Newton, put it into the form that lets you write in a name, put in a little form that says “put the message,” and then I just have to write ten lines of code that know how to send this message.

It can drag out of the names database the person’s email address, the phone numbers, whatever parts I wanted.

I actually started to write this once on the Macintosh. On the Macintosh, there is no unified data of names, There’s no database. In my Macintosh, I have a HyperCard stack that has people’s names in it. I have a contact manager with people’s names in it. I have names all over the place. So I had to write my Own names management piece of software. Here it’s all together.

What's so cool is that application developers get access to this, and don’t have to worry about “How am I going to store names?” That’s already taken care of for you. But let’s say you have a special way of addressing email in your company—well, you can just add to this data easily. For somebody else, it may be their astrological sign.

By having this unified data that’s shared, you get a much more powerful environment to write applications in, and it’s much easier. This application took about an hour to write on the Newton. On Macintosh I got the window up, and that’s about it.

If developers can do custom apps much easier, it makes everybody’s life as a consumer and a user much better, because you don’t want to sit there and think, “Well, I’ll use that stock program, but it’s overkill for what I really want.” You can whip together these little apps that are exactly the way you want.

When you say “you,” do you mean the average user, or the developer?

The HyperCard-type developer could do this without even breathing hard.

DA: For the end-user, what it means is that when they have a Newton application, on one of these PCMCIA cards, they bought it becausé they were going to use this particular Newton. Later, when we've taken the technology and done a lot more different things based on that same technology, everything that uses that Newton information at that level and up, like these applications would, can run on things that use Newton technology underneath.

So we take this and we create different forms, different ideas, different concepts of products, but based on the same underlying information structure and the same toolbox. A lot of those apps will be able to run across those platforms.

Okay, this is really neat, but I’ve got half my life on my two Macs. Clearly, as you said, PageMaker is not a fit for this hardware, but sometimes you’re going ¢o want to take the information in Newton and move it into PageMaker.

DA: The idea of Newton Connection is that you can exchange information between the Newton and the desktop. The whole idea of being a communication device means that you have to be able to go outside of this device very easily to bring information in and send information out. Supporting things like faxing and printing is part of being a communication device; but also, a large part of that is supporting ready exchange of data with the Macintosh and with the PC. Newton Connection runs on Macintosh and runs on Windows; you can upload and download stuff, you can synchronize information between this Newton and the desktop.

SC: You want the nerd angle to all this?

Please.

Okay, another good thing about all this is—here I’m writing an application, and I’m adding, like, a WELL address to the concept of a person. That will automatically get uploaded, that’s preassembled.

But let’s say I’m an astrologer, and I’ve got some kind of special database my application needs. With no work from the developer, that will automatically get uploaded to your desktop machine; but what’s cool about it is you can edit it in both places.

Say it’s Astrology Inc., and you can come in and get your horoscope while you wait. They could be sitting there on their desktop machine doing the forecast for this person; when I come in with my Newton, because I’m out there in the field doing the field horoscopes, I can synchronize up and I can see what you told this person the last time. With zero work from the developer, the data is automatically shared and editable on both sides, and that’s very useful.

With the Connection Pro you can use Apple Events to take information out of the connection program and share it amongst desktop programs.

One of the cool things a third-party developer showed at the rollout—they really get the idea of Newton, which is that you write down “Hertz $59,” and you click the Assistant button.

If I were doing your expenses on a handwritten form, you would just say, “Hertz $59,” and I’d go, “Oh, Hertz. Car rental.” And I'd go to the slot that says “Car rental” on the form, and fill it in. When you as a desktop computer user say, “Oh, I like my desktop machine because I can fill out the form directly”— well, you have to futz, and you have to go figure out where the car rental is, what date it is, all this stuff.

So what these guys have done is, you write “Hertz $59,” click the Assistant, it comes up and says, “Oh, this is a car rental. We’re assuming you mean today because you're doing it today, but you can also change that.” And when you hit OK it will record that. When you dock to the desktop computer, it pulls that data out and uses Apple Events to go throw it in, however you manage your expenses. So if you use Excel, and you have named fields in Excel, it will be able to find a Car Rental field and go “Boom!” and paste it in.

It sounds kind of mundane, but when you think about all the steps that it gets rid of...

Computers have been this wonderful way of making us do a lot of data processing. They don’t do it down in some basement place any more; you don’t hand your receipts to somebody and they just disappear; we all do it now. What we try to do with Newton is make it so much simpler—“How many times do I have to tell you that Hertz is a car rental?” Really, once. We all assume Hertz will be around for a while; in fact the third party has figured that out, and we never have to say that it’s a car rental. They understand the major hotel chains, airfare, car rental, things like that.

You just take a little bit of intelligence and apply it across the board, and suddenly things get really fun. The whole shtick about computers up to now has been “How do I make it easier for you to do your work?” And what we’re trying to say is “How do you make it easier to get stuff done?”

We could throw the best user interface in the world at you to make you do all the steps. Word processors and PageMaker made it fun that you do a lot of work to get beautiful-looking things. Well, why not make the computer do a little more work, and still get beautiful-looking things?

That’s kind of the direction we’re going—you don’t fuss with margins and fuss with fonts, you just say, “I want it to look good like this,” and you point it to a format, and we go out and try to format it to match that.

DA: So the customer’s doing more of the little note-taking things, little pieces of information, like you do when you're traveling and you wind up coming back from your trip with this pocketful of little pieces of paper and little receipts and notes, and you’re trying to figure out what was what day and what was happening. Doing that in Newton means the system is going to take that stuff for you and try to do as much as it can to process that into the same file format. It’s more like what you see a lot of people doing, when they’re doing note-taking and organizing of their own.

At what point did you get users involved in testing this? What happened when outside people started getting involved?

SC: Early on, you start bringing your friends and spouses, that kind of thing, in. You're at home working and you say, “Hey, what do you think of this?” and they give you this blank look and you go, “Oops!” But they’ve been involved since literally the very first few months.

DA: From the time we were trying to figure out what stylus to use.

SC: It’s kind of funny—you have to be 100% empirical when it comes to users. You can’t theorize. You gain experience, but it’s all measured. You cannot prove a hypothesis at all. Whenever you deal with users, you must be prepared to be completely humble, constantly.

Who needs this right now?

SC: Like Donna just said—say you just paid your car bill, you’re not going to whip out your PowerBook and say, “Just a minute, I’m getting it into Excel...” I’m sure there are people who do this, but they’re ultimate nerds.

You could see whipping one of these Newtons out and writing “Hertz $79,” and then just stuffing the receipt in an envelope and never having to deal with it.

DA: I’d say people who need this are people who have a lot of information flowing in and out of their lives because they have a lot of communicating to do and things to keep track of. That’s what it helps to do.

SC: The other thing she said, which is very important—since there’s not 8086 assembly language instructions buried in our applications, applications you buy today will live for a long time. So things that you get used to today are only going to get better, and hopefully you'll see Newtons inside cameras. You'll see Newtons inside everything. You’ll be able to use those applications everywhere it makes sense.

Of the applications that currently exist that you’ve seen, what do you think are the most interesting?

SC: My favorite’s the expense manager thing, because I just waste so much time doing expense reports. Games are fun. What’s also amazing is how fast people are writing serious applications. Much faster than with the Macintosh.

DA: It’s hard to choose which app I like the most, but one I definitely like a lot is the [Fodor’s] travel guide, because I get lost all the time. When we went to Boston, it actually was genuinely useful to have that travel guide. It does all the navigation and charts a path for you. “What is the address of the hotel I just checked into, now that I’m not there anymore and I can’t remember how to get back there?” It’s right there on the screen.

The fact that it’s with you means that you don’t have to go look stuff up, you don’t have to keep asking people, you have it right there in your hands, and you just use it. That’s one I like a lot.

Do you see a huge migration of book publishers to this kind of medium?

SC: Yeah, I think there’s going to be a lot of content. One of the concepts that’s going to be interesting is the concept of Reference Plus. Think of the Birthday Present Advisor, where you're sitting there and saying, “I’ve got to get something for my father’s birthday.” It might ask you a few questions—“Does he like golf?” or something like that— and help you narrow down the decision, then just start randomly selecting things. That’s a lot of content, but you have to have a little bit of intelligence, take advantage of the processor. There’s the equivalent of a Mac IIfx hiding in this box.

[Taking out PCMCIA card] This is the future.

DA: There are lots of different devices coming out in that PCMCIA form. This receives pages. It’s really cool and really convenient. With this kind of a thing, your pages will show up as text on a screen. Right now we're in beta on this—you can get the kinds of pages that people send you explicitly— “Mary’s in the lobby, go down and get her”—but you can also just get the stuff that shows up every day. The newswires, the news service, the things that just come through once you’ve subscribed and said that’s something that interests you. You just get that stuff on your Newton. It just shows up.

How much of a problem is the equivalent of disk-swapping with the PCMCIA cards when you change applications? Do you have to change cards all the time?

SC: Well, the typical way to use it is you might have a peripheral and a memory card. This pager actually has a little memory in it, so the pages that come in when it’s not plugged in get saved here.

But as we all know from any computer, it has too few slots and too few disk drives. It’s like everything else. And of course we all want it to be infinitely thin and infinitely light and infinitely cheap. There’s going to be some people that have ten of these gadgets, and they’re going to curse the day we didn’t make a ten-slot Newton. But we're designing it for affordability and portability right now.

Some application-mongers will keep one memory card in the slot and put all their applications on it, because all the apps have a tendency to run very small. This is a 2MB card; it would be a long time before I filled that. People who are much more on the go would probably keep a pager card there. But swapping’s fine, you just pop it out and pop it in.

Do you expect a lot of third-party people to make Newtonoid devices?

DA: Definitely. We're licensing the technology.

SC: That’s what’s even more exciting. I was kind of glib about Newton in a camera, but there are going to be some really cool Newtons out there that we have never even thought of.

But also, just take a look at how many devices you buy today that have an LCD screen on them and a computer in them. And you say, “Why am I paying for all this proliferation of computers?”

Probably the most obvious right now is GPS devices, these things that tell you where you are in the world. I just saw a Sony device that looks almost identical to this, has a million buttons on it, has the same size screen. If you talk to an engineer, the guts of the GPS part are actually very cheap relative to what you pay for this whole device—the device is two or three times more expensive than the Newton—because the quantity’s not there.

So give me the GPS guts, put it in here on a card, and now I have a beautiful user interface, the ability for expandability by putting apps in on here. I have everything I want, but I can use it in many places. I can now use that also for keeping my addresses. You could imagine a world where every device has an address book in it, a notepad in it; or you could just, say, put peripherals onto the one smart device that you want to carry around with you—cellular phone, GPS, all that stuff. You might want a scanner...

People are going to do cool things.

What computer ads would you like to see in the future? Please comment below. If you enjoyed it, please share it with your friends and relatives. Thank you.