Alan Sugar of Amstrad Speaks to Practical Computing (1985)

A Quick Look Behind the Scenes at Amstrad.

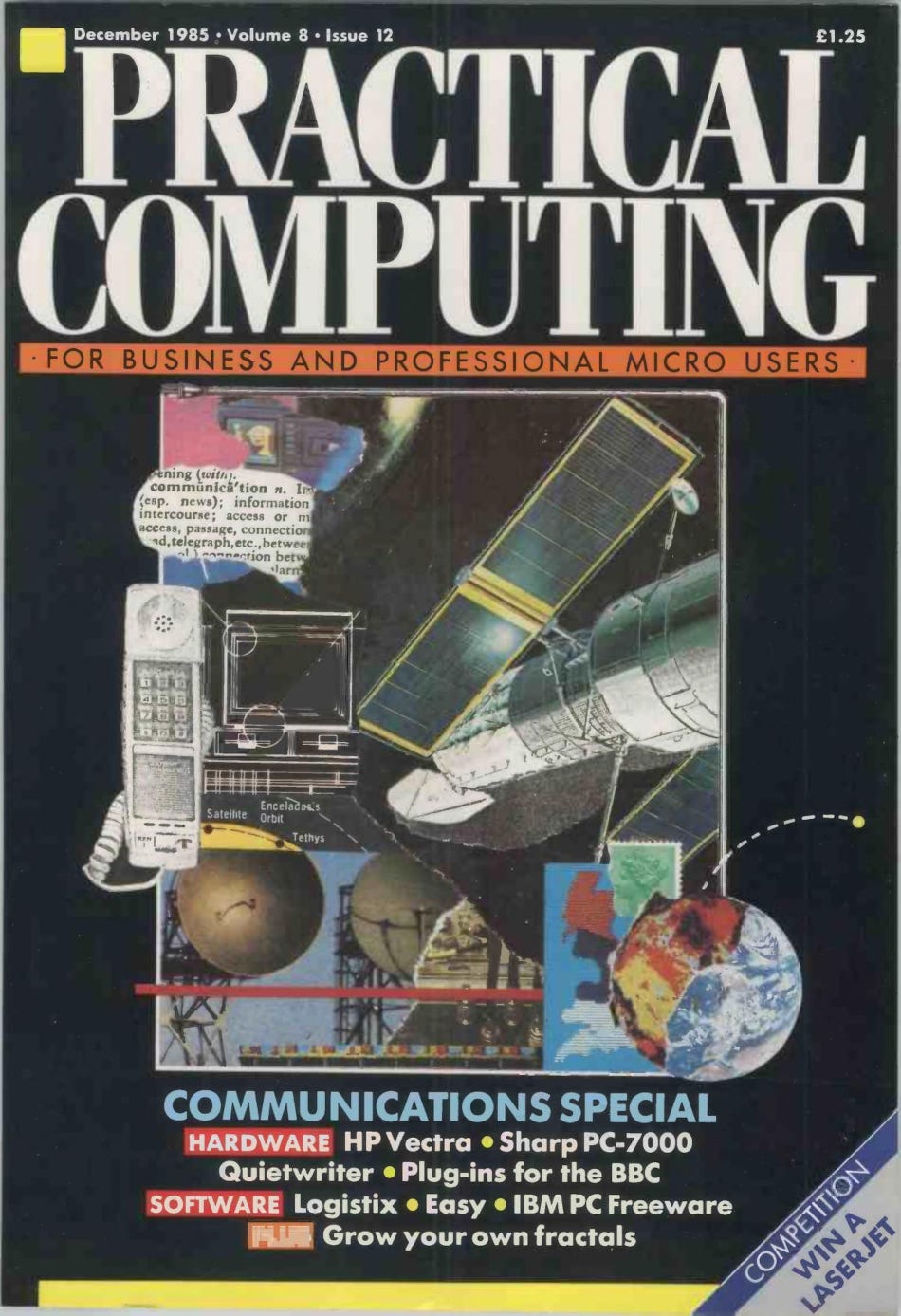

from the December 1985 issue of Practical Computing magazine

Alan Sugar was born in 1947, and founded Amstrad Consumer Electronics in 1968. The name derives from Alan Michael Sugar Trading. Initially the company distributed car accessories and electrical goods. Twelve years later, the company was floated on the Stock Exchange, and by then was selling a range which included hi-fi and televisions. The turnover then was £9 million. In 1984 Amstrad launched the CPC-464, its first computer, and turnover hit £84.9 million with profits of £9 million. That year, Alan Sugar was also named Guardian Young Businessman of the Year. Turnover for 1984-85 was £136 million with profits of £20 million, with overseas sales accounting for 53 percent of the group’s activities.

Interviewed by Glyn Moody

To what extent does the initial specification of a new machine come from you?

It starts off coming from me saying ideally what I would like and then it has to be explained to me what is possible. I’m basically non-technical so I may ask for something which is physically and practically impossible for the kind of price area I want something produced at.

What were the core ingredients of the PCW-8256?

I observed that possibly 70 percent of IBM PCs are used for word processing. It appeared to me that a lot of the hardware was then redundant. You’d run out and bought a £2,000 or £3,000 piece of kit and perhaps you were only using maybe 10 percent of the potential of the machine. So the brief was we wished to produce a word processor which was very good, which was not complicated and had to have everything integrated. It had to have its disc drive and obviously the printer there. And the printer had to be versatile. Once we outlined the specification it became clear that by-the-by this was a computer you were talking about, not a word processor, and we might as well capitalise and use the other half of it as a computer, and so we stuck in CP/M Plus. So if you want to run Supercale 2, or dBase II or Ashton-Tate’s Friday, or Multiplan or whatever, you can do that. And you can do it faster than some of the famous PCs which are on the market. There was no point producing a piece of kit for £399 if it was going to be a toy and didn’t work.

To what extent will the PCW-8256 be the first of a family of machines?

We believe that in that particular sector there is no space for improvement because | think we have captured everything that one could conceivably ask a word processor to do. Maybe there will later be enhancements as time goes by and technology advances, or different printers we might be able to package with the thing. But that’s it. It sits there in its own right as a kind of epidemic product which we hope is going to emboss its name in the world as the Amstrad, just like you may talk about the Hoover.

To what extent does it represent a change of direction for you?

It’s a very big change of direction for us. We believe we have created a new concept in computing that’s going to be used seriously, and obviously with a massive breakthrough in price.

Who do you see as your main rival?

We haven't got any rivals on that product. People would have to come down in price to compete with us. There are companies out there which make dedicated word processors only which sell for £7,000 to £8,000 without a printer. I think those people have got a bit of a problem on their hands, because they cannot justify the price of their machine; they cannot justify its existence with this product around.

How do you see the serious computing market developing in this country?

I think that the problem that will evolve for others is being able to compete with us. With the greatest of respect to the other manufacturers of what we class now as the more serious computing end of the market, I do not know how they can justify the prices that they charge for their products. All I can say is that perhaps they have been out there alone too long. I think that certain other companies will have to change their thinking.

What is your attitude to local area networks?

Within an office environment networking is useful. However, if you are producing a machine at the kind of price level that we are, we find that the market for these machines is for the individual — the executive or typist or whatever — to have it on his or her desk alone, to do their little bit of what their job entails, away from everyone else, away from the DP manager who’s never got any bloody time for them. That machine and this type of philosophy of computing is at a price level where that particular executive or person doesn’t necessarily have to go to a board meeting to make a decision whether they can buy one or not. It is within his or her capability of buying a £399 piece of kit.

What proportion of Amstrad’s turnover do you expect to be from micros in future years?

For the next couple of years I think we’re going to see 60 percent of the business geared towards computers.

What is your attitude to the U.S. market?

We're being very cautious on that market. We've observed in the past failures from British and European companies who have tried to set up over there, and we don’t want to follow that route. We’re looking for customers in America, rather than set up our own thing. We'll sell to them as long as their commitment is irrevocably covered by letters of credit and orders.

In what direction would you like Amstrad to develop?

We're in the consumer electronics industry. That must cover computers and things which are allied to it, and that’s where we plan to stay.

What computer ads would you like to see in the future? Please comment below. If you enjoyed it, please share it with your friends and relatives. Thank you.